Anika T. Prather

June 2, 2021

Blog: Weaving Humanity Together: How Weaving Reveals Human Unity in Ancient Times

To start with, she lived a respectable life, frugal and hard;

she earned her living by weaving and spinning wool.primum haec pudice uitam parce ac duriter

agebat, lana ac tela uictum quaeritans.— Terence the African (P. Terentius Afer), The Girl from Andros, 74–75

This line drew my attention because I am an avid fiber artist. When I am not reading, teaching, and writing about Classics and its connection to Black people, I am in my wool room, lost in the magical world of fiber arts. This line from The Girl from Andros has led me on a new journey of discovering fiber arts in ancient times.

The first discovery I made was that the process I use to spin yarn on a drop spindle is an ancient art. By attaching the fiber to the spindle, rolling the spindle across the inner thigh, and then letting it spin at a rapid twirl, the ancients would create yarn. In The Fabric of Civilization, Virginia Postrel explains that the drop spindle’s importance is connected to its being the earliest form of human technology. Looking at these simple machines also reveals unity of cultures, for their use can be seen in ancient Rome, Greece, Egypt, and other cultures around the world. Ancient weaving technology suggests a cultural exchange of knowledge, not separated by race, as we tend to see and experience the world today.

Herodotus’ Histories describes his journey to record human history by traveling outside of Greece, to Africa and the Middle East. The ancient world was such a different place from what we might expect, one where crossing ethnic divides was quite common. This crossing of ethnicities is accompanied by a sharing of knowledge — including skills such as spinning and weaving — between peoples. And ethnic and racial differences were not marked by color, as they are in the modern world: as Frank M. Snowden, Jr. writes in Before Color Prejudice, “Greeks and Romans did not establish color as an obstacle to integration in society.”

The universality of weaving can be seen in ancient myths. The Egyptian goddess Neith is credited with the creation of weaving, and is often depicted with a weaving shuttle on her head. Egyptian myths also hold that, as a creator goddess, Neith created the world by weaving it. Athena is parallel to Neith as goddess of spinning and weaving, acknowledged as such as early as Homer’s Odyssey: “By how much the men are expert above all other men in propelling a swift ship on the sea, by thus much the women are skilled at the loom, for Athena has given to them beyond all others a knowledge of beautiful craftwork, and noble minds” (ὅσσον Φαίηκες περὶ πάντων ἴδριες ἀνδρῶν | νῆα θοὴν ἐνὶ πόντῳ ἐλαυνέμεν, ὣς δὲ γυναῖκες | ἱστῶν τεχνῆσσαι: πέρι γάρ σφισι δῶκεν Ἀθήνη | ἔργα τ᾽ ἐπίστασθαι περικαλλέα καὶ φρένας ἐσθλάς, 7.108–111, translation by Elizabeth Wayland Barber). I take these shared traits of Neith and Athena as a sign of how weaving transcended countries and cultures. The relationship of Neith to the Greek goddess Athena reveals the practice of “weaving” humanity together through the sharing of each other’s cultures and stories.

Figure 1: Statuette of the Egyptian goddess Neith, Louvre Museum. Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

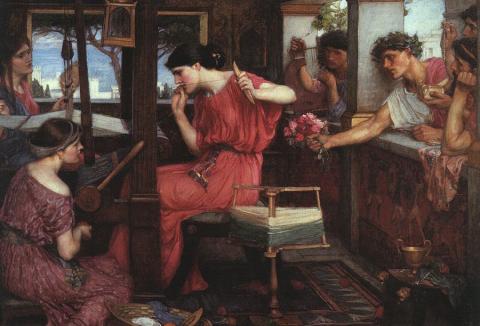

Neith and Athena are not the only mythic representations of the importance of weaving to human civilizations. There is the story of Arachne, who was punished by Athena for challenging her in the art of weaving (Athena turned her into a spider). Then there is the story of Penelope, wife of the long-lost Odysseus, who, in order to delay having to choose a new husband, claims that she will choose one after she finishes weaving a burial shroud for her father-in-law.

In the Jewish tradition, Proverbs describes the virtuous woman as one who spins and weaves (31:13, 19, 22, 24). Meanwhile, in the Christian Acts, we encounter Lydia of Thyatira, the founder of one of the early churches in Philippi. She was a dealer of purple fabric and the first person Paul connected with in Thyatira. The wealth she gained from selling her fabric gave her the financial resources to support the new religion growing there. We can see weaving as a fabric that connects not only ethnicities and cultures, but also beliefs and religions.

As each culture shared the art wisdom of spinning and weaving, each culture would make the skill their own, and different forms were developed. Ancient Egyptians used vertical looms, where the threads were tied to the bottom, and ancient Greeks used a warp-weighted loom, where the threads were weighted down with weights. The earliest signs of weaving have been found in the tombs of ancient Egypt.

Another technique, band weaving, involves weaving decorative, small, narrow bands to be used as belts, straps and other ornamental purposes. One method for band weaving uses small tablets to create the decorative markings. In Weaving: Methods, Patterns & Traditions of an Ancient Art, Christina Martin explains the process:

The tablets, usually square and also known as cards, have a hole in each corner, lettered clockwise, A to D. In the past they were made of bone, wood, tortoiseshell, or horn, but they can also be made from light card about 4 inches square. When rotated, either in unison or in groups, they raise and lower different warps to create patterns in the weave.

Tablet weaving is believed to be the oldest form of patterned weaving, probably dating back to the Bronze Age. It has been found in Africa, Asia, and Europe. The earliest extant mention of tablet weaving may be Pliny: “Truly, Alexandria introduced weaving using a lot of threads that they call ‘polymita,’ Gaul dividing with little shields” (Natural History 8.74.196: plurimis uero liciis texere quae polymita appellant, Alexandria instituit, scutulis diuidere Gallia). It is uncertain whether Pliny’s “little shields” denote tablets or something else, but his comments have to speculate that tablet weaving began in Egypt. Some have suggested that the belt of Ramesses was made through tablet weaving. So many different cultures have used tablet weaving that it is hard to pinpoint its origins, which I again take as a sign of weaving’s role as a shared wisdom, passed on from century to century and culture to culture.

The more I researched band weaving, the more the process reminded me of Kente Cloth. At most of my own graduations, I wore a Kente Cloth band around my neck. This was a way for me to honor my enslaved ancestors and all they suffered for me to be able to achieve success. I thought of the intricate designs in the Kente Cloth band and began to wonder if a similar process as tablet weaving was used to create Kente Cloth. Kente Cloth is also rooted in mythology, as James Padilioni, Jr. writes:

According to Asante mythology, it was here that the great trickster Ananse the Spider, ever skillful and cunning, spun a web of intricate detail in the jungle. When Nana Koragu and Nana Ameyaw, brothers and weavers by trade, came upon Ananse’s web, its immaculate beauty enchanted them. After studying Anansi’s handiwork, the pair returned to the village and began to weave Kente.

Weaving and textiles among the Akan and Ewe people of Ghana is documented as starting as far back as 1000 BC and, through the centuries, weaving has come to take on deep symbolism. Kente cloth dates back to the 17th century, when chief Oti Akenten (where the word “Kente” comes from) brought in various types of beautiful woven fabric. He then commissioned that Kente cloth be woven for royalty. I find kinship in band weaving and the weaving of Kente cloth, as Padilioni describes it:

Figure 2: Kente cloth loom. Photo courtesy of Creative Commons.

Kente cloth sheets are assembled out of sewing together long strips or bands of fabric, each 6”–10” wide. Each one of these bands are themselves composed of panels of alternating designs. Each weaver creates this patchwork appearance through a complex interplay of the warp (the threads pulled left to right during weaving) and weft (threads oriented up and down).

To my surprise, images of Kente cloth weavers appear similar to the images of band weavers. Although clear evidence does not survive for how the people of Ghana learned band weaving, we see the similarities in how the weaving is done, another symbol of the universal nature of weaving and its many forms.

As Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., said in his Letter from a Birmingham Jail, “We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny.” Note the powerful weaving metaphor. Weaving reveals an example of one of the ways humanity can be drawn together. This shared art form shows the beauty that is possible when we come together. Each culture, as it traveled through times and continents, shared the skill of weaving, and each culture made it their own. Like the intricate bands of the Kente cloth, weaving reveals, as Virginia Postrel writes, a “Fabric of Human Civilization…a whole made up of distinct pieces, each interwoven, with its warp and weft.”

Human Tapestry

We are one

Sewn together by centuries

Of dwelling on this planet together

Our lives intertwined

To make a beautiful image of unity

Different shades

Different hair

Different lips

Same blood

Same minds

Same world

Same heart

Together creating a story of our humanity

That is not all one color

But one rainbow

Reflecting the beauty of humanity

In one tapestry

Header image: Penelope and the Suitors, by John William Waterhouse. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Authors