Catherine Bonesho

February 7, 2019

'Addressing the Divide' is a new column that looks at the ways in which the modern field of Classics was constructed and then explores ways to identify, modify, or simply abolish the lines between fields in order to embrace broader ideas of what Classics was, is, and could be. This month, Prof. Catherine Bonesho, an Assistant Professor at UCLA who specializes in the ancient history of Judaism and the Near East, speaks to classicist and Herodotus scholar Prof. Rachel Hart.

Where you work—and who you work with—can make a world of difference. A good chair, a charged computer, and my books were at one point all I thought I needed in my research. However, while still a graduate student at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, I realized that it’s not just where you work or what your work is, but the colleagues you work with.

I met Classicist Rachel Hart five years ago when we were assigned to the same office space in graduate school. Our programs had merged into a single department and brought both the faculty and the graduate students from both departments together. Rachel has a PhD in Classics from the University of Wisconsin-Madison and most recently was a Visiting Assistant Professor in Classics at Beloit College. Her current monograph project investigates autopsy and physicality in the writings of Herodotus and Ctesias, with a focus on the literary representation of foreign peoples. Though she specializes in Greek historiography, she currently also works on Late Republican Latin literature, and has taught Latin at both the University of Wisconsin-Madison and Beloit College. What we learned while working in that small office was the value of interdisciplinary collaboration for scholars of antiquity.

(Photo Courtesy of Rachel Hart)

Our conversations about antiquity and the intersections of the Mediterranean and the Near East have changed how we view our own research projects, as well as our respective fields. Inspired by Andrew Tobolowsky’s recent piece in Eidolon, we discuss the current state of our respective fields (Classics and Ancient Near Eastern Studies/Jewish Studies) and the intersections of our research interests. We also show that the payoff of our interdisciplinary collaboration illuminates not only our research projects, but also how best to teach various topics dealing with antiquity.

The concept of marginality is a place for significant overlap between our approaches to research and teaching. Margins are not only spatial, but can also be social or temporal, and different fields have different conceptions of what is marginal. Indeed, there has been renewed interest in the study of the margins of antiquity, as well as the reception of texts and figures in both Classics and Ancient Near Eastern Studies. This difference in perspective and our own interests in the margins of the ancient world sparked our new conversations about permeating these boundaries.

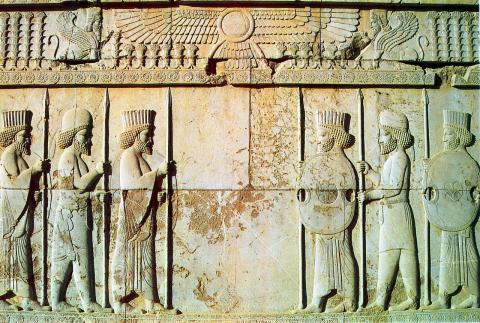

(Photo by Jona Lendering and used via CC BY-SA 4.0)

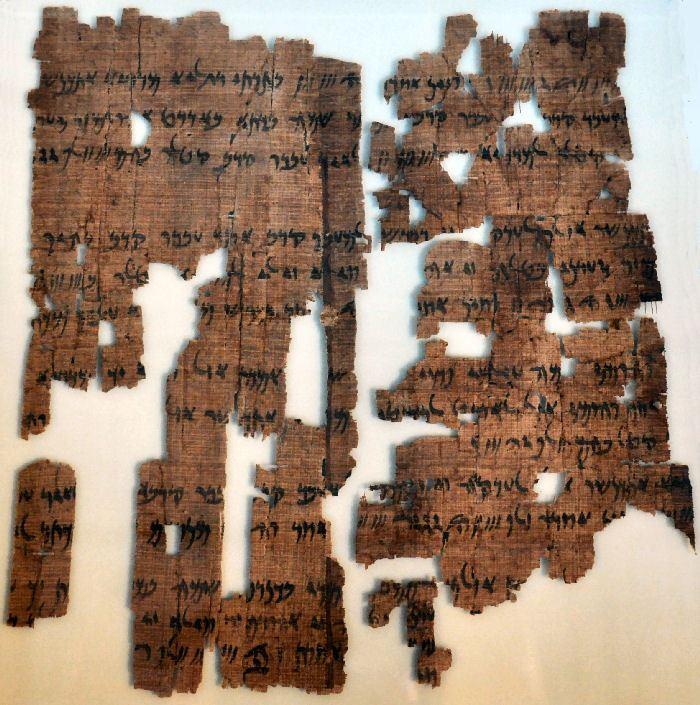

Because we came from two separate fields, when we were assigned to the same office, we initially wondered what kinds of discussions we would have, if any. However, we soon began a dialogue about the spatial “margins” of our respective fields that expanded our research questions. Specifically, Rachel’s work on Herodotus’ descriptions of the Persians and my work on ancient Jewish (rabbinic) descriptions of the Romans meant that we were looking at literary texts that discuss “the Other” but generally from different directions. Though Herodotus and the ancient rabbis are separated by a few hundred years and write in different languages and places, they still talk about “the Other” in a similar manner that responds to the political and cultural events of their respective lifetimes.

In our research, we both look at interactions between a traditionally “Classical” culture and a “Near Eastern” culture, but with different groups acting as the margin. Similarly, both of our approaches avoid outdated considerations of “historical accuracy” in ancient literature and treat these accounts as the literary constructions of individuals within their socio-historical contexts. Given the similarity of our projects, it only made sense that we talk to one another about the writings of Herodotus, Ctesias, and the ancient rabbis, and how best to read these texts in light of the margins.

During these interdisciplinary discussions of our research projects, we have also introduced each other to variant methods and theoretical sources that have helped us to better read and understand ancient texts, such as theories of religion, gender, and post-colonialism that are commonly used in our own field and that the other might not have readily thought to apply. Our conversations overall have helped us to introduce more nuance to our respective research projects in ways that we had not considered when only discussing our research interests with scholars in our own fields.

Indeed, one wonders how you can study Herodotus or Ctesias without interacting with those who specialize in the Ancient Near East, specifically the Achaemenid Empire, or how you can look at the Roman holidays listed in the Talmud without engaging with specialists in rabbinic literature. Classics and the study of the Ancient Near East should not only be studied by themselves and the attempt to do so has led to missed opportunities to understand the competition and interactions of the ancient world. This interdisciplinary direction is generally where our fields are moving and we are not alone in this comparative and collaborative approach to the texts and objects of antiquity. Our ancient sources are treasure troves for information on the ancient world, but the best treasures are found when one engages with these sources beyond the boundaries of disciplinary lines that were constructed by modern scholars.

Just as antiquity is not restricted to the arbitrary boundaries of various fields, neither are our students, their experiences, and their interests. An interdisciplinary and collaborative approach to the study of the Ancient Mediterranean in the classroom is foundational for an inclusive pedagogy that considers the diversity of the student body. Many of our first collaborative discussions were about how to incorporate the margins into our respective intermediate Latin classes, as well as courses in translation. For example, in my Latin class on Ovid’s Metamorphoses, I asked students to look at ancient funerary inscriptions after reading the story of Phaethon. However, instead of looking at only Latin inscriptions, I had students look at Jewish inscriptions found in Rome, as well as bilingual Latin and Palmyrene Aramaic inscriptions. Such a simple exercise introduces students to the “margins” of the Roman Empire and shows students that Roman antiquity does not necessarily fit tightly within the confines of Classics and the study of Greek and Latin.

Rachel too did a similar exercise with her mythology students while reading and discussing the Aeneid. After students had already read the Homeric epics and had a good understanding of the Aeneid’s context in relation to Greek precedents, she thought it was crucial to also grasp the imperial connotations of the poem. The story of Dido proves to be a model figure for this type of exercise, since Dido as a character incorporates so many layers of Otherness for the Romans: she is a woman, a monarch, and a foreigner. In concentrating on Dido, Rachel was able to show her students similar depictions of individual women in Latin literature, as well as epigraphic evidence from Roman Africa that highlights the fact that Carthaginians had their own history and existence outside of Roman portrayals. Our continued interdisciplinary dialogue encouraged us to create these inclusive pedagogical activities and effectively brought the margins of the ancient world into our own classrooms.

Although we no longer share an office, or even live in the same time zone, our conversations continue to positively affect our research, pedagogy, and views of our academic disciplines more broadly. Our collaboration is but one example of the fruitful effects of going beyond the boundaries of one’s own field. We see our interdisciplinary study of the ancient world as a way of molding ourselves as scholars, as well as hopefully impacting future scholars who intend on joining our respective fields. By working at the intersections of Classics, the Ancient Near East, and Jewish Studies we can illuminate and refocus the study of antiquity toward the margins. Turns out, our separate fields are not so separate after all.

Header Image: Apadana Hall, 5th century BC carving of Persian and Median soldiers in traditional costume. Image via Wikimedia under CC BY-SA 3.0.

Authors