Kelly McArdle

May 20, 2018

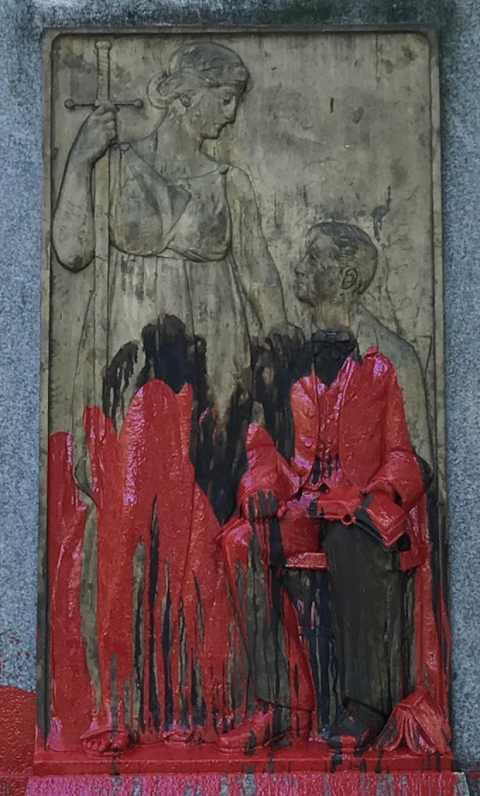

On April 30th 2018, Maya Little, a graduate student in the Department of History at UNC-Chapel Hill, was arrested after covering the Confederate statue known as “Silent Sam” in a mixture of red ink and her own blood. The monument has stood in a prominent position on UNC’s campus since its dedication in 1913, but has for years been the object of debate and protests, which have intensified since the national push to remove confederate statues following the events in Charlottesville, Virginia. Funded by the Daughters of the Confederacy and a group of UNC alumni, “Silent Sam” was originally dedicated as a tribute to UNC students who lost their lives fighting for the Confederacy in the Civil War, though like many such statues, it was erected during the Jim Crow era decades after the war had ended.

Maya Little pours ink and blood on Silent Sam

(Image by permission of the Workers Union at UNC-CH).

When Julian Carr, a UNC alumnus and open supporter of the Ku Klux Klan, gave his dedicatory speech, he clearly expressed his belief that Confederate soldiers fought for the preservation of “the very life of the Anglo Saxon race in the South.” Notably, Carr’s speech turned to Greek mythology as a comparandum. He compared southern mothers mourning their dead sons to Niobe mourning her own slaughtered children, conveniently failing to mention that Niobe brought on her children’s deaths:

As Niobe wept over her sons slain by Apollo, so the tears of our women were shed over the consummate sacrifice of their loved ones. And as the gods transformed Niobe into a marble statue, and set this upon a high mountain, as our native goddesses erect this monument of bronze to honor the valor of all those who fought and died for the Sacred Cause, as well as for the living sons of this grand old University.

Allusions to the grief of mothers in antiquity did not stop at the reference to Apollo’s and Artemis’ killing of Niobe’s children. Carr went on to connect southern women with Andromache, Penelope, Verginia, and Lucretia, and further argued that “the Spartan lived again in the Confederate Student Uniform.”

When we in the Classics department at UNC-Chapel Hill heard about Little’s brave act of civil disobedience, Carr’s use of classical figures in his dedication speech loomed large in our thoughts. As members of an academic field whose objects of study have been employed in the discourse around “Silent Sam” and a field whose very goal is to contextualize and nuance relics of the past, we felt that it was necessary to respond. Many of our department’s graduate students came together to express support for Little’s action and to insist that the university administration take any action necessary to remove the statue from our campus. In doing so, we followed the example set by our department’s faculty, among faculty in other departments at UNC, who called for the statue’s removal in the fall of last year (2017). A handful of Classics students and faculty also attended a rally in support of Little and packed the court house at her first hearing, where she was officially charged with misdemeanor vandalism.

In the time following our statement’s release, it has been shared widely. Local Confederate apologists, who found the statement on Facebook, questioned the credentials of our entire department: a familiar tactic used by political extremists to undermine the authority of any perspective that differs from their own. Both in spite of and because of such attacks on our capability as Classicists, we understand that our statement is a necessary step toward righting some wrongs of our discipline’s past. Carr was not the first and will certainly not be the last white supremacist to employ figures of classical antiquity for rhetorical effect, as Donna Zuckerberg and Sarah Bond have recently demonstrated. We agree with Zuckerberg when she argues that “The classicists of the past have a share of the blame for shaping an alt-right-friendly vision of European history without diversity.”

To many in the Classics Department at UNC fighting for the removal of “Silent Sam,” Julian Carr and the current defenders of the statue are not simply ‘misusing’ figures from antiquity in their attempts to glorify Confederate movements. Rather, they are picking up on the problematic interpretations of past classicists. As UNC alumnus Timothy Williams noted in his book, Intellectual Manhood: University, Self, and Society in the Antebellum South, on the history of education at the institution prior to the Civil War: Classics was seen as the basis for advancement and self-fashioned leadership in the South. Today, we must then recognize that classicists are inheritors of a tradition that we love, but also of a tradition that has at times used classical antiquity to justify romantic, racist, and exclusionary actions. It has thus become easy fodder for white supremacy. Bearing this fact in mind, those who signed the statement felt a responsibility both to acknowledge our discipline’s contributing role in racist rhetoric and to undermine that rhetoric actively by speaking out against it. In this vein, we who signed the statement rejected any reading of antiquity as an idealized past: it is instructive but not exemplary.

with ink and blood running down

(Image by permission of the Workers Union at UNC-CH).

The view that “Silent Sam” must be properly contextualized also played an important role in our statement. As students of antiquity, we who signed the statement understand the value of preserving historical monuments and artifacts, but we also believe that those monuments and artifacts must be grounded in historical events and eras, rather than being presented as unbiased memorials of the past. Historian and UNC professor Lloyd Kramer recently wrote in response to the “Silent Sam” controversy, “Monuments convey historical interpretations rather than historical facts.” We agree that “Silent Sam” conveys a particular interpretation of southern history. Given that Carr both lauded the Confederate preservation of “the purest strain of the Anglo Saxon” race in the South and bragged about the fact that he himself “horse-whipped a negro wench” 100 yards from where "Silent Sam" stands, we who signed the statement believe the statue conveys a historical interpretation that glorifies the subjugation of black people. By allowing “Silent Sam” to remain in a prominent position on our campus, the university administration allows that interpretation to take precedence over historical fact. As Little wrote in an open letter to UNC Chancellor Carol Folt:

Today I have thrown my blood and red ink on this statue as a part of the continued mission to provide the context that the Chancellor refuses to. Chancellor Folt, if you refuse to remove the statue, then we will continue to contextualize it. Silent Sam is violence; Silent Sam is the genocide of black people; Silent Sam is antithetical to our right to exist. You should see him the way that we do, at the forefront of our campus covered in our blood.

We who signed the statement stand in full support of Maya Little’s’s forcible contextualization of “Silent Sam,” which shows the monument for what it truly is: a vestige of and shrine to white supremacy. As long as “Silent Sam” remains on campus, it will necessarily lack the contextual information needed for viewers to understand the circumstances of its dedication and its intended meaning. We believe we must continue to provide that context until the university administration relocates the statue.

Moving forward, we who signed the statement plan to continue speaking out about “Silent Sam” and institutional racism on our campus, including the 16-year moratorium on renaming campus buildings, many of which are named for Confederate supporters and white supremacists. We are committed to defending Maya Little, using our expertise in the study and preservation of the ancient world to show that her action was a dedicated historian’s necessary response to a white-washed version of history. We are glad to have the continued support of our faculty in this endeavor. Our hope is to see “Silent Sam” moved to a local museum or historical site, such as UNC’s Ackland Art Museum or the Bentonville Battlefield State Historic Site, where future historians and proper signage can provide visitors with the statue’s proper context. Such a gesture would be only the beginning of acknowledging and rectifying the racist legacy of our university. Our continued involvement also speaks to our desire to rectify part of the legacy of our discipline. We hope always to learn from the past, but never to romanticize it.

Header Image: Close-up of the statue base of “Silent Sam” on campus at UNC-Chapel Hill with ink and blood running down (Image by permission of the Workers Union at UNC-CH).

Authors