Nina Papathanasopoulou

November 5, 2021

The Ancient Worlds, Modern Communities initiative (AnWoMoCo), launched by the SCS in 2019 as the Classics Everywhere initiative, supports projects that seek to engage broader publics — individuals, groups, and communities — in critical discussion of and creative expression related to the ancient Mediterranean, the global reception of Greek and Roman culture, and the history of teaching and scholarship in the field of classical studies. As part of this initiative, the SCS has funded 111 projects, ranging from school programming to reading groups, prison programs, public talks, digital projects, and collaborations with artists in theater, opera, music, dance, and the visual arts. To date, it has funded projects in 25 states and 11 countries, including Canada, the UK, Italy, Greece, Spain, Belgium, Ghana, Puerto Rico, Argentina, and India.

This post focuses on four projects aiming to reinvigorate interest in the field of Classics and the ancient world: an exhibition about the life and classics careers of two black women, Helen and Dorothy Chesnutt, in Ohio; a talk and workshop on the art of bas-reliefs and the technique of making them in the Berkshires; a production of Plautus’s Amphitruo in Canada; and a virtual performance of the Laodamiad, a contemporary play based on the mythical story of the Greek hero Protesilaus and his wife Laodamia.

An Exhibition on Helen and Dorothy Chesnutt

Paul Hay, Visiting Assistant Professor of Classics at Hampden-Sydney College in Virginia, has created a permanent exhibit for the Classics Department at Case Western Reserve University (CWRU) in Ohio to commemorate the historical participation of women of color in classics at CWRU and in Cleveland. Feeling a connection to CWRU, having been an undergraduate student there and now having taught there for four years, Hay wanted to reinvigorate student involvement in Classics while demonstrating that the participation of women of color in Classics is part of a longer tradition dating back a century. He created a poster exhibit detailing the Classics careers of two Black women, Helen and Dorothy Chesnutt, with photographs from the CWRU archives and from the holdings of the Western Reserve Historical Society, and with QR codes that link to important information regarding the Chesnutt women. In addition to the poster, Hay composed an encyclopedia entry for Helen Chesnutt for the online Encyclopedia of Cleveland History.

Helen and Dorothy’s work was not previously familiar to many Classics students at CWRU, though both women had studied at CWRU and made noteworthy contributions to the field: Dorothy Chesnutt completed a BA in Classics at CWRU and became a high school Latin teacher in Cleveland, while Helen started her graduate studies there, completed a master’s degree at Columbia University, taught Latin in Cleveland for over 40 years, published two articles on Latin pedagogy, and co-authored The Road to Latin, a Latin textbook published in 1932. As part of Hay’s effort to spread awareness about Chesnutt’s work, a copy of The Road to Latin was also placed on reserve in Special Collections at CWRU.

Hay’s efforts have given The Road to Latin a new lease on life. Eighty years after its first publication, Amy Cohen, Professor of Classics and Chair of the Theatre Department at Randolph College in Virginia, will be using it in her class this coming Spring. The textbook is in some ways unique in its approach to teaching Latin: for example, it does not introduce second-declension masculine nouns until Chapter 13, inviting the students to imagine — at least for a while — a world in which all nouns are feminine.

To create the poster, Hay worked closely with Michele Ronnick, Professor of Classics at Wayne State University, who has worked extensively on the Latin career of Helen Chesnutt, and with the Classics Department of Wake Forest University, who graciously allowed him to use their painted portrait of Helen Chesnutt in the poster. Wake Forest commissioned Leo Rucker to paint this portrait and two others as part of their Classics Beyond Whiteness programming, which was, in turn, supported by an SCS Classics Everywhere grant.

Hay’s research has produced some intriguing finds: highlights include finding a photograph of Dorothy Chesnutt in the costume of a Greek goddess dating to 1911 and discovering that Helen’s initial pursuit of a master’s degree in 1925 was instigated by her wish to avoid teaching summer school that same year.

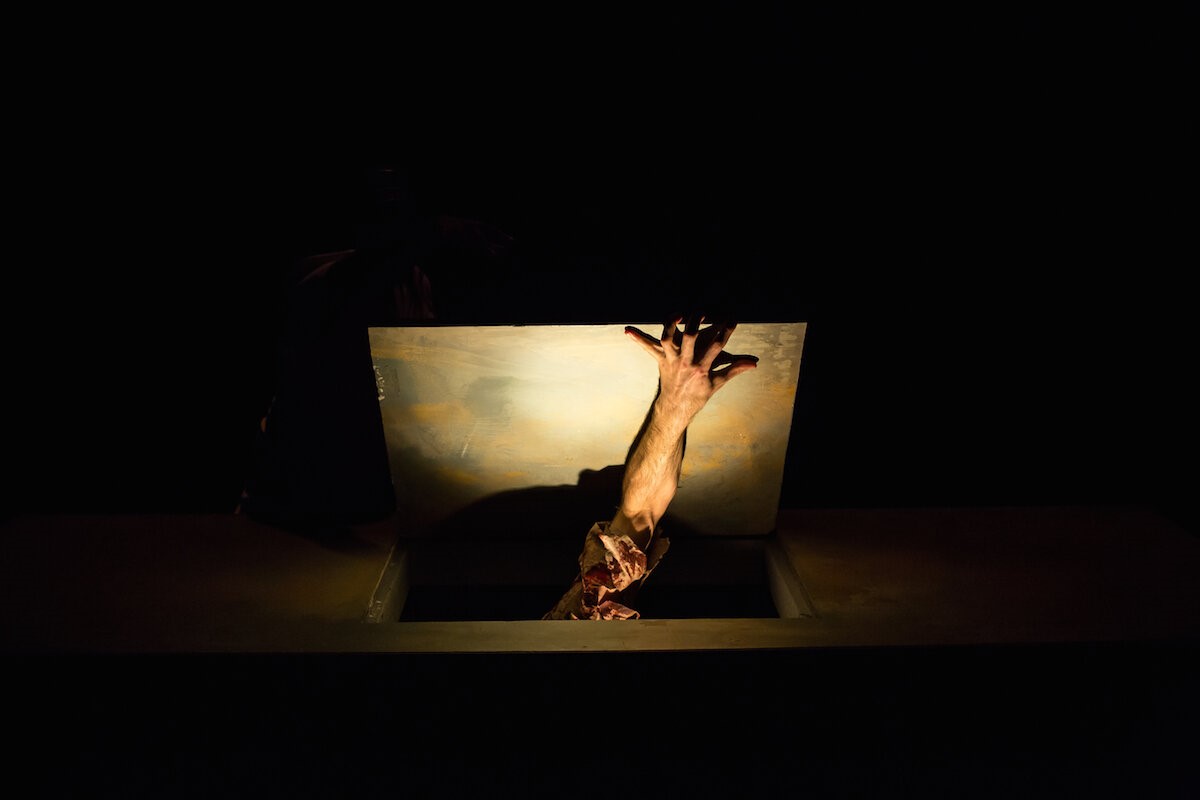

Figure 1. Paul Hay holding a copy of Helen Chesnutt’s Latin textbook and standing next to the exhibition poster placed permanently in the Classics Department at CWRU. Photo by Paul Hay.

The presidential panel during the annual meeting of the Society for Classical Studies in January, organized by SCS President Shelley P. Haley, will be dedicated to Helen Chesnutt. The panel is entitled “’Say Her Name’: The Career, Lived Experience, and Interiority of Helen Maria Chesnutt (1880-1969),” and will take place on January 7, 5:30–7:30pm Pacific time.

From Coins to Caskets: A Talk and Workshop on Bas-Relief Art

Susan Bachelder, a Classics aficionado and retired chair of the Egremont Historical Commission, is planning a free talk and workshop on the importance and technique of low-relief art for residents of the Berkshires at Trinity Church’s Parish House in Lenox, MA. The talk, entitled “From Coins to Caskets: Hidden Messages in Ancient Bas Relief Art,” will be given by Ananda Fetherston, an award-winning artist and faculty member at the Grand Central Atelier in New York City, on November 12, 2021, at 6 pm.

Fetherston’s focus will be on the history and function of bas-relief art, from the caskets of antiquity to the tombstones of New England, and also on the making of coinage. Those interested in attending by Zoom can follow this link. The workshop will be run on the following day, November 13, by Fetherston along with Annemarie Haftl, a local clay artist in Lenox, MA. Haftl and Fetherston will teach participants how to make their own bas-relief artwork, and to work in a compressed space to maximize effects of light and shadow.

With funding from the SCS’ Ancient Worlds, Modern Communities initiative, Bachelder acquired around 15 professional casts for the talk and workshop from The Caproni Collections in Woburn, Massachusetts. Bachelder noted that interest in Greek and Roman art — which will be discussed on Friday evening and in Saturday’s workshop —exploded across Europe when Johann Winkelmann’s book, The History of Art in Antiquity, was published at the end of the 18th century. “It reshaped our visual relationship with the ancient past,” she believes. “In 1835, the first business making plaster casts for sale of ancient statues was started in Boston. By the late 1800s, the Caproni Brothers’ studio could cast over 4,000 pieces they had acquired from museums around the world.”

Figure 2. A wall of bas-relief models, ranging from shallow to deep-cut, from the Caproni Collection, several of which will be used in the workshop to demonstrate the range of carving that can be used. Photo by Susan Bachelder.

Bachelder has always been interested in coins as a means of conveying information. She became fascinated with bas-relief art when she realized the layers of meaning that can be added to the representations based on the positioning of the figures and the direction in which they are looking. “The artistic device of low-level relief was especially potent when used in the objects of burial practice,” she explains, “as public mourners could share in the experience of the deceased’s life as well as their afterlife on public stelae.”

Those interested in participating can contact Bachelder directly at spbach23@gmail.com.

Figure 3. The Caproni Studio of Woburn, MA, with museum-grade copies of famous sculptures. From the left: Michelangelo’s head of David, in the background George Washington and Thomas Jefferson, the winged Victory of Samothrace, a variety of portrait heads, and Abraham Lincoln. Photo by Susan Bachelder.

Plautus’s Amphitruo in Canada

Toph Marshall, Professor of Greek at the University of British Columbia, has not only completed a new verse translation of Plautus’s Amphitruo, one which gives special attention to the play’s rhythm and musicality, but used it to direct a modern version of the play. Set vaguely in the 1930s with contemporary soldier costumes, the play is in some ways modernized. But it also conscientiously employs certain original stage practices, such as role doubling, in which the same actor plays two roles, thereby drawing attention to or even creating a rich array of parallels and contrasts in the play’s structure.

Produced by the United Players Theatre Company of Vancouver, the play ran for 16 performances from September 10 to October 3. Marshall, who became the artistic director of the company in 2020, engaged the support of colleagues at UBC, who assigned the play as reading in their courses. Students then attended the production, melding experiential with academic learning. Several events surrounding the myth and theater history of the play accompanied the performances. The production was well received by the diverse community of Vancouver which, as one of the play’s reviewers noted, rarely has the opportunity to watch ancient Roman comedy.

Figure 4. The company (Ayush Chhabra, Joan Park, Camryn Chew, Claire deBruyn, Erin Purghart, Matt Loop) tear the script during Mercurius’ prologue, from the United Players’ production of Amphitruo. Photo by Nancy Caldwell.

Marshall is drawn to the darkness of the Amphitruo story and the ethical questions it poses. The play follows the story of Heracles’ mother Alcumena, who is raped by Jupiter without her knowledge. The god disguises himself as her husband Amphitruo while the latter is away at war, so Alcumena sleeps with him not knowing his identity. Marshall is challenged by the violence of the story and the discomfort it causes. Violence is directed not only against Alcumena, but also against enslaved characters, who are repeatedly beaten throughout the play. There is also a tension within the characters, as each shares elements of other stock characters: the enslaved man is also a parasite, the soldier is also an old man, the wife is also a meretrix (sex laborer).

Figure 5. Amphitruo (Ayush Chhabra) returning home to his wife Alcumena (Joan Park) during the United Players’ production of Amphitruo. Photo by Nancy Caldwell.

The production was supported by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC). Additional funding from AnWoMoCo was used to make a high-quality film recording of the performance, which is now available as a free educational tool for myth, history, and literature courses. Faculty or students interested in seeing the film for educational purposes can email Marshall at toph.marshall@ubc.ca. By creating the film, Marshall hopes “to challenge people to think about Roman comedy in a new way.”

A Virtual Performance of The Laodamiad

Inspired by the few lines that survive from Euripides’ lost tragedy Protesilaus, Chas LiBretto, playwright and former visiting scholar at the Center for Hellenic Studies, wrote The Laodamiad, a play about our ways of dealing with grief. LiBretto’s initial interest in the play came as a response to his own family experiences, specifically the suicide of a loved one. The play centers on the story of Laodamia, a woman who is unable to cope with the death of her husband, Protesilaus—the first soldier, according to the Iliad, to fall in the Trojan war. In the myth, Laodamia is so consumed by her grief that she makes a statue of her husband and continues to carry on her relationship with him even after his death.

“The feeling of grief following the loss of a loved one,” LiBretto explains, “is like a small stone placed in your pocket. You are not always aware of it, but it is always there with you. And, once in a while, you reach down in your pocket and feel it.”

The play was initially workshopped in 2016 at the Roundabout Theater in NYC, and then in 2017 at the Getty Villa in Los Angeles, CA . On December 1, 2021, a virtual performance of the play will be presented as part of the Harvard Center for Hellenic Studies’ second season of “Reading Greek Tragedy Online.” Directed by Hunter Bird and with original music for a harp composed by Kim Sherman, The Laodamiad will be read by professional actors and contextualized by leading scholars in the field. LiBretto is hopeful that an in-person live production of the play will also take place in 2022.

LiBretto has previously found interest in adapting and making accessible lesser-known ancient plays for a modern audience. His musical Cyclops: A Rock Opera, based on Euripides’ satyr play with music composed by J. Landon Marcus, was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize in 2012.

LiBretto explains the significance of theater adaptations:

One of the most crucial aspects of theatre is its immediacy and the humanizing effect of seeing stories outside of our own frame of reference presented live. While grounded very much in Classics and myth, much of The Laodamiad deals with trauma, PTSD, and the human effect a never-ending forever war has on a people. My hope is that Laodamia’s story brings hope to those who are struggling.

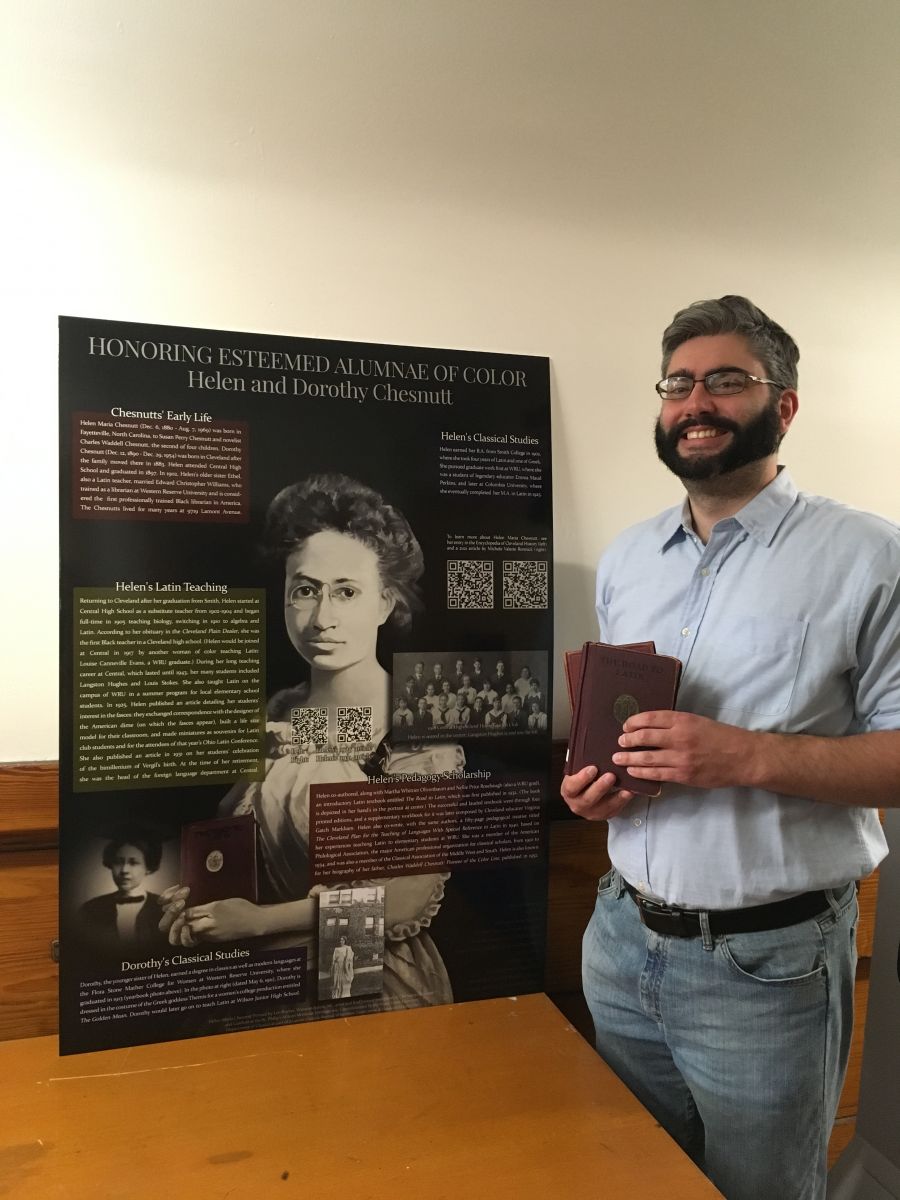

Figure 6. Protesilaus (Nathaniel Peart) rises from the grave. Photo by Kelly Stuart.

Figure 7. Laodamia (Kea Trevett) and the statue of Protesilaus (Quinn Roll). Photo by Kelly Stuart.

Header image: Roman Relief depicting the Twelve Labors of Hercules. 2nd century C.E. Uffizi museum, Florence.

Authors

.PNG)