Sonya Nevin

February 14, 2020

Greek vases, with their distinctive red and black, are one of the most recognizable faces of ancient Greece. Their decorative scenes of deities, myth, and everyday life offer a beautiful and informative window into classical culture. With the Panoply Vase Animation Project we’re encouraging people to enjoy and learn about ancient vases and society by placing the artifacts center-stage in short, lively animations made from the vase-scenes themselves. The animations keep as close as possible to the original artwork, using the existing figures and decoration and drawing on existing iconography. But the figures can now move, and the animations explore the possibilities within the vase scenes: runners can sprint past, dice are thrown, and those poised to strike can use their weapons. The tone of the animations varies. The Cheat is a light-hearted romp; Hoplites! Greeks at War will send shivers down your spine.

The project draws on my knowledge as an ancient historian and the technical and artistic skills of animator Steve K Simons. We live and work in Cambridge in the UK, where we met twenty years ago, although we first developed the project in Dublin, Ireland, while I was a doctoral researcher. We started with stop-motion animations telling stories from antiquity. This went on to experimenting with vase figures. We soon realised the educational potential in animating vase scenes and began planning ways that they could be used in museums alongside the vases they were made from. Now that vision has actually been achieved and will hopefully continue to expand as more museums hear about what we offer. On the way, we’ve learned a huge amount about how the animations can be used. We built the project website to display the animations, and we include material on there to help people learn more and to support use of the animations in teaching. Each one comes with information about the vase and the subject of the animation, plus suggestions for activities and further reading (ancient and modern). I do quite a bit of teaching with the animations to people of all ages; it’s a lot of fun and it’s wonderful to see the creative ways that people respond.

The vase animations are very effective within outreach work because of the way that they grab people’s attention and show the beauty and energy of the ancient artwork. Non-specialists can feel unenthusiastic about rows of apparently similar vases or static images of them, so it really perks up their attention when they then see those scenes moving. Once people’s curiosity is piqued, they’re fundamentally more open to learning. In a museum, that means encouraging people to linger in the vase gallery longer and, by seeing movement and action, to see the dynamism that is inherent within the original images. In the classroom, that can simply mean adding some extra energy to the way that vases are taught or a fun yet artefact-based route to teaching ancient world topics.

The animations can also help people to understand what they’re looking at when they see vase scenes. We made The Symposium from a cup in the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, for example, it shows a diner reach out and take a lyre from the wall and begin to play it. That will make it easier to comprehend what is suggested by the lyre in the original scene, while other details such as the grapes, cushions, and variety of cups are also made clearer. Once people are attuned to seeing details, they’re more inclined to look for further details themselves when it comes to real artefacts.

Figure 1: Screenshot from The Symposium using an Athenian black-figure pottery cup, 6th-5th century BCE, depicting an outdoor symposium (drinking party) beneath a vine arbour, around a Gorgons head, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, UK.

The animations can also be used to support learning about classical topics. Because they feature themes such as myth and athletics, they work as companion media for discussions about those sorts of activities. The Cheat, featuring a footrace, provides an accessible route into sessions on athletics or festivals, for example. (As you’ll see, it also plays with the fourth wall in a really interesting way). I’ve used Clash of the Dicers, which features Exekias’ scene of Achilles and Ajax gaming, to ease undergraduates into Sophocles' Ajax. We’re careful about the details that go into the animations so (unless explicitly stated, as in Dance Off), the animations draw on Greek history and vase iconography to tell their stories. A lot of my research is on Greek warfare, and that’s reflected in Hoplites! Greeks at War, which depicts key aspects of the military experience – training, divination, fighting, celebration and so on - and which draws on ancient iconography of war. I know one university lecturer who shows it to his warfare class and then simply says, “Discuss”. The students find analysing the animation an effective way to explore their thoughts about ancient conflict. The animations work in this way whether you have a group of young people or university students – only the depth of the discussion needs to change. On the website, the animations are grouped by topic as well as by project, to make it easier to integrate them into a class. The Oxford symposium animation makes a lovely resource for teaching about symposium culture.

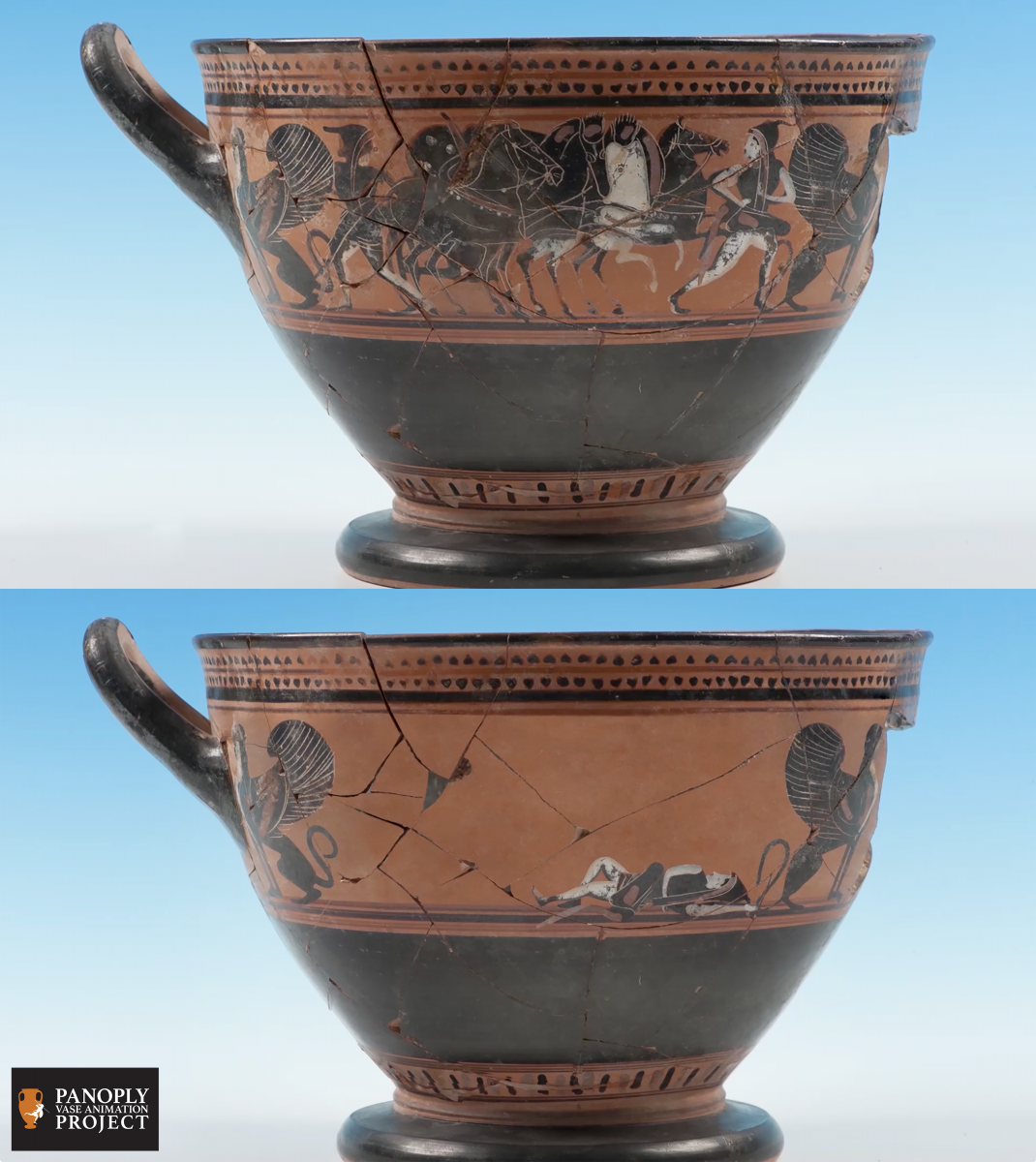

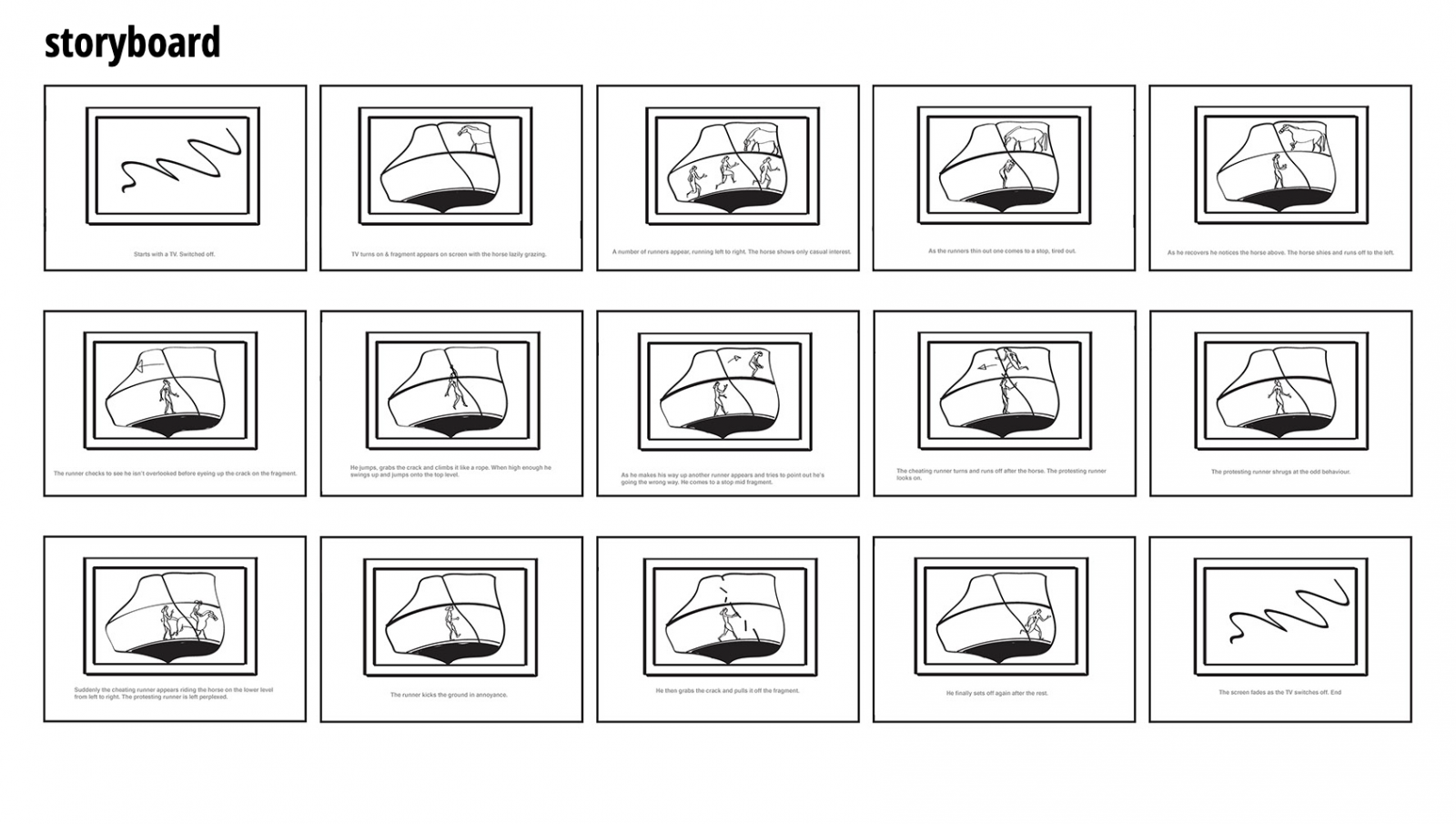

Watching the animations offers a springboard into other activities. Animations are planned through storyboarding, with illustrations and short descriptions of the key moments in a narrative. Creating these is a great way to develop skills in story construction and communication and, when they’re based on vases, finding details to elaborate on prompts close, incentivised analysis. We encourage people to look at the vases, watch the animations, and then to create their own alternative storyboards or to choose other vases to storyboard from. I really enjoy seeing what people come up with – they’re often very thoughtful and people find different aspects of the vase scenes to draw out. This sort of storyboarding is also a good way for students to process what they’ve been learning about classical culture. They can draw-on their knowledge of, say, festivals, to create storyboards based on a festival theme, or if they’ve been studying Athens, they can plan how they’d depict a story from an everyday scene on an Attic vase. Even seeing a class-full of alternative storyboards can be an instructive experience. It’s a clear demonstration that people respond to artefacts in different ways; that there’s no one absolute way to read them.

Figure 2: Within the Panoply Vase Animation Project, there is a "Uses" section that encourages teachers to instruct students on how to storyboard an animation. Teachers can download a blank storyboard and access a terminology guide to get started.

Storyboarding and similar activities can also be an effective lead into conversations about why the vase-painter might have chosen to depict the scene they did, rather than, say, a different moment from the same myth or a different combination of characters. It can also support discussions about the distinction between single image and narrative sequences. We’ve included downloadable material on the Panoply Vase Animation Project website to help teachers with these sorts of activities, such as a guide to storyboarding, storyboard examples, themed character-creation sheets, and other suggestions for discussions and activities.

Some of our projects have given young people or graduate students more direct involvement in the animation process by allowing them to determine how the stories unfold. Firstly we joined Amy Smith, curator of the Ure Museum in Reading, for the Ure View and Ure Discovery projects, in which we worked with museum staff and university students to help local young people learn about ancient culture, ancient vases, and the process of making animations. The teenagers planned stories based on their interpretations of the vases and Steve used their storyboards as the basis for new animations. The teenagers also made a range of other artwork in response to the Ure collection. All of these elements were combined into a tablet trail that visitors can take around the museum. Each group responded in their own way to the collection and were highly motivated in their study of vases by the knowledge that they would be doing something creative with them. (You can find out more about these projects in Smith and Nevin 2015).

Figure 3: Screenshot of the animation of a 6thC BCE skyphos from the Ure Museum of Greek Archaeology (26.12.11) and a scene from Amazon, the animation made from it.

A similar dynamic worked in Ireland, at the University College Dublin Classical Museum. Masters students studying ancient material culture planned an animation to compliment an exhibition they were curating. This was a great opportunity for them to put themselves in a professional mind-set, thinking about what animation would help museum visitors to understand the vase and how they would approach teaching within the museum (see The Procession). This was followed by a schools’ competition funded by Classical Association of Ireland Teachers. A wonderful array of storyboards was submitted and Steve transformed two teenagers’ winning entry into an animation (Bad Karma). Both animations can now be seen online and in the museum alongside the vase they were made from. Although having an animation actually created is the most thorough way of going through this process, even just planning museum displays in this manner is an effective way of encouraging learners to thinking about how artefacts are displayed and about their own role in shaping how others experience them.

Figure 4: Screenshot from the Irish schools' storyboard competition, which resulted in The Procession and Bad Karma, both based on ceramics from University College Dublin's Classical Museum.

The animations come without dialogue, which has helped to make them international and more appealing to deaf viewers. The audio comes solely from music. In most cases, we have drawn on music created by scholar-musicians who make recreations of ancient instruments, music, and performance. Stefan Hagel of the Institute for the Study of Ancient Culture in Vienna, Austria, can be heard on the Ure View animations, while many more feature the music of the Melpomen Ensemble, led by musician and musical archaeologist Conrad Steinmann of the Schola Cantorum Basiliensis in Basel, Switzerland. Hoplites! Greeks at War, was different again. The animation was created within a wider Panoply project called Every Soldier has a Story, funded by the AHRC through Oxford University, while funding from the Ure Museum, the University of Reading Classics Department, Yana Zarifi-Sistovari director of the Thiasos Theatre Company, and Bloomsbury Academic Publishing allowed for the creation of new music and the staging of a live event. The soundtrack was written by composer John White and Steve adapted it to the animation. Thiasos gave a live performance at the first showing of the animation.

It was tremendous to hear such interesting live music and to see the animation on a cinema-size screen. In time, an alternative soundtrack was created when the National Museum in Warsaw included the animation in their exhibition, Hoplites: On the Art of War of Ancient Greece. Curator Alfred Twardecki enlisted students from the University of Warsaw to chant Tyrtaeus’ Spartan poetry in Greek; they can be heard exhorting warriors to fight as the animated battle unfolds – wonderful. A recent animation, Sappho Fragment 44, Hector and Andromache A Wedding at Troy, features music scored by Armand D'Angour. He specialises in reconstituting the sounds of ancient music and what you hear on the animation is a version of the music that Sappho's poetry would originally have been accompanied by - absolutely fantastic. It’s a real pleasure to bring these different art-forms together and the unusual sounds of ancient-style music add another intriguing element to the animations.

Figure 5: Storyboard from The Cheat, an animation based on a fragment of a vase housed in the Ure Museum.This was commissioned by the Open University for their open access study unit, The Ancient Olympics: Bridging Past and Present, winner of the 2012 OCW open courseware award.

More than anything else, it’s been enjoyable to see how brilliant scenes from the animations look re-imagined in new contexts. So, for example, you can get the real Nike on sportswear (and a whole range of other items) and there are some great designs that use the horses from The Cheat and Amazon. It’s bringing a bit of vase-style into people's everyday life. There’s a lot still developing in conjunction with the project as well. We have new interviews coming out on our blog, which we view as a place where people share information about what they do with ancient pottery. The interviews reflect a variety of specialisms and have featured Sir John Boardman and Thomas Mannack on symposium iconography, Anastasia Bakogianni on Electra, Véronique Dasen on magic and play, Philip de Souza on ships and piracy, Laura Jenkinson on the Greek Myth Comix, and student Gabrielle Turner on doing a museum internship. It’s an accessible way of sharing insights into the work of classicists and we always include questions about their use of vase iconography.

At the moment we are working on a major international project, Our Mythical Childhood. The Reception of Classical Antiquity in Children’s and Young Adults’ Culture in Response to Regional and Global Challenges. This is a huge project organised by Katarzyna Marciniak of the University of Warsaw and funded by the European Research Council. It is generating breakthroughs in the understanding of the role of antiquity in modern young people’s culture. For our part, we have made five new animations from vases in the fine collection at the National Museum in Warsaw. They feature Sappho, Heracles, Dionysus, Iris, Zeus and Athena. The animations will be available online later this year. Right now we're making short documentaries about them which will provide extra information and context. We are also contributing animations to Locus Ludi: The Cultural Fabric of Play and Games in Classical Antiquity. This ERC-funded project, led by Véronique Dasen, is exploring ludic culture in antiquity.

We're making vase animations and also stepping into new territory with some animations made from other antiquities. We’re also looking forward to working with more people and more collections in the future. Ancient artifacts are wonderful objects and a tremendous resource. We want to do our bit to celebrate them and, in creating new things inspired by them, to show that antiquity is a vibrant part of the present as well as the past.

Header: Screenshot from the Clash of the Dicers, based on Exekias' Attic black figure amphora with Ajax and Achilles playing a game, c. 540-530 BCE, Archaic Period, found in Vulci (Gregorian Etruscan Museum, Vatican Museums, Vatican City).

Authors