Three Ancient Historians, Katherine Blouin, Usama Gad, and Rebecca Kennedy

November 2, 2020

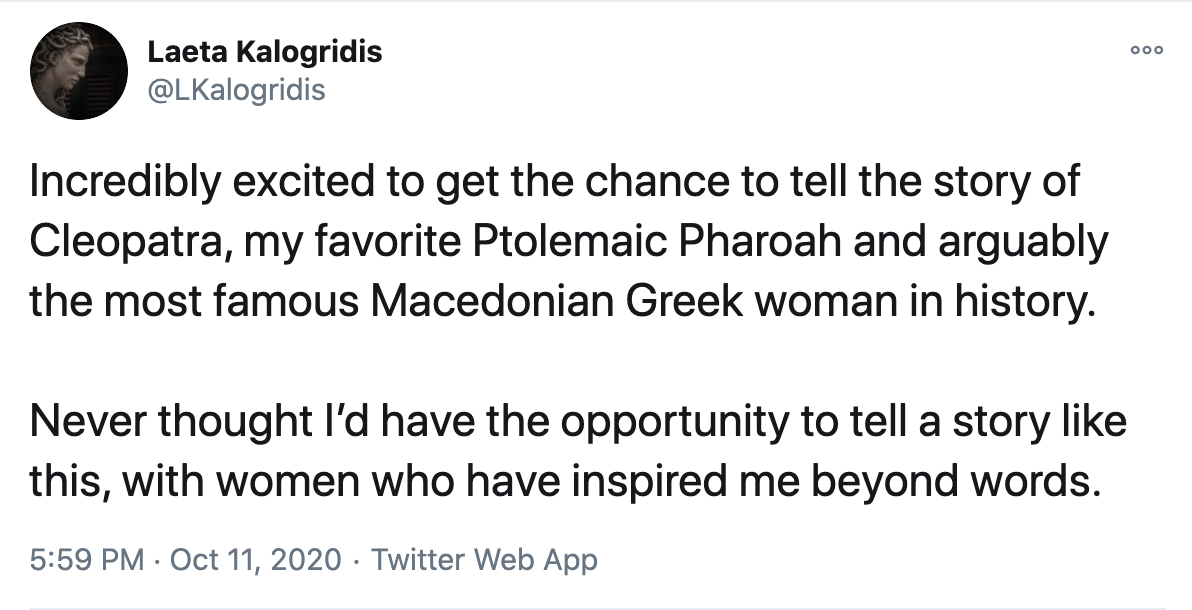

On October 11 2020, American screenwriter and producer of Greek descent Laeta Kalogridis posted this tweet:

The same day, she posted a picture of a marble head found close to Rome and believed by some scholars to portray Cleopatra VII.

The next day, October 12,, Israeli actress Gal Gadot announced on social media that she was teaming up with Kalogridis as well as with American director Patty Jenkins (with whom Gadot has previously worked on the set of Wonder Woman) “to bring the story of Cleopatra, Queen of Egypt, to the big screen in a way she’s never been seen before”. She added that “[t]o tell her story for the first time through women's eyes, both behind and in front of the camera.” Along with her Twitter and Instagram announcements, Gadot posted a picture of the painting “Cleopatra on the Terraces of Philae” by Orientalist painter Frederick Arthur Bridgman (1847 - 1928).

Figure 2: Cleopatra on the Terraces of Philae, 1896. Oil on canvas, Frederick Arthur Bridgman (CC0 1.0).

In a second tweet, she added a layer of feminist messaging by writing:

"We are especially thrilled to be announcing this on International Day of the Girl! We hope women and girls all around the world, who aspire to tell stories will never give up on their dreams and will make their voices heard, by and for other women."

The news was received with a tsunami of comments and reactions, many calling the choice of Gadot as Cleopatra a controversial choice. The hashtag #Cleopatra trended on Twitter for over 24 hours after the announcement, and in the days that followed, several articles and editorial pieces were published regarding the controversies.

Outside the Arabo-Muslim world and diaspora, reactions mostly focused on Cleopatra’s ethnicity or perceived race. Even Sean Ono Lennon, son of Yoko Ono and John Lennon, had something to say. Meanwhile, reactions from within Egypt and the wider Arabo-Muslim world were of a strikingly different tone. Indeed, most of them focused on two themes:

1. The idea of the historical Cleopatra as an Egyptian queen:

Figure 3: Mocking a famous scene in Hinidi’s comic movie “ Hamam in Amsterdam”, where a European tells him “Our pyramids”, Ihab, with a screenshot of the movie, writes “ You mean our own Cleopatra!”.

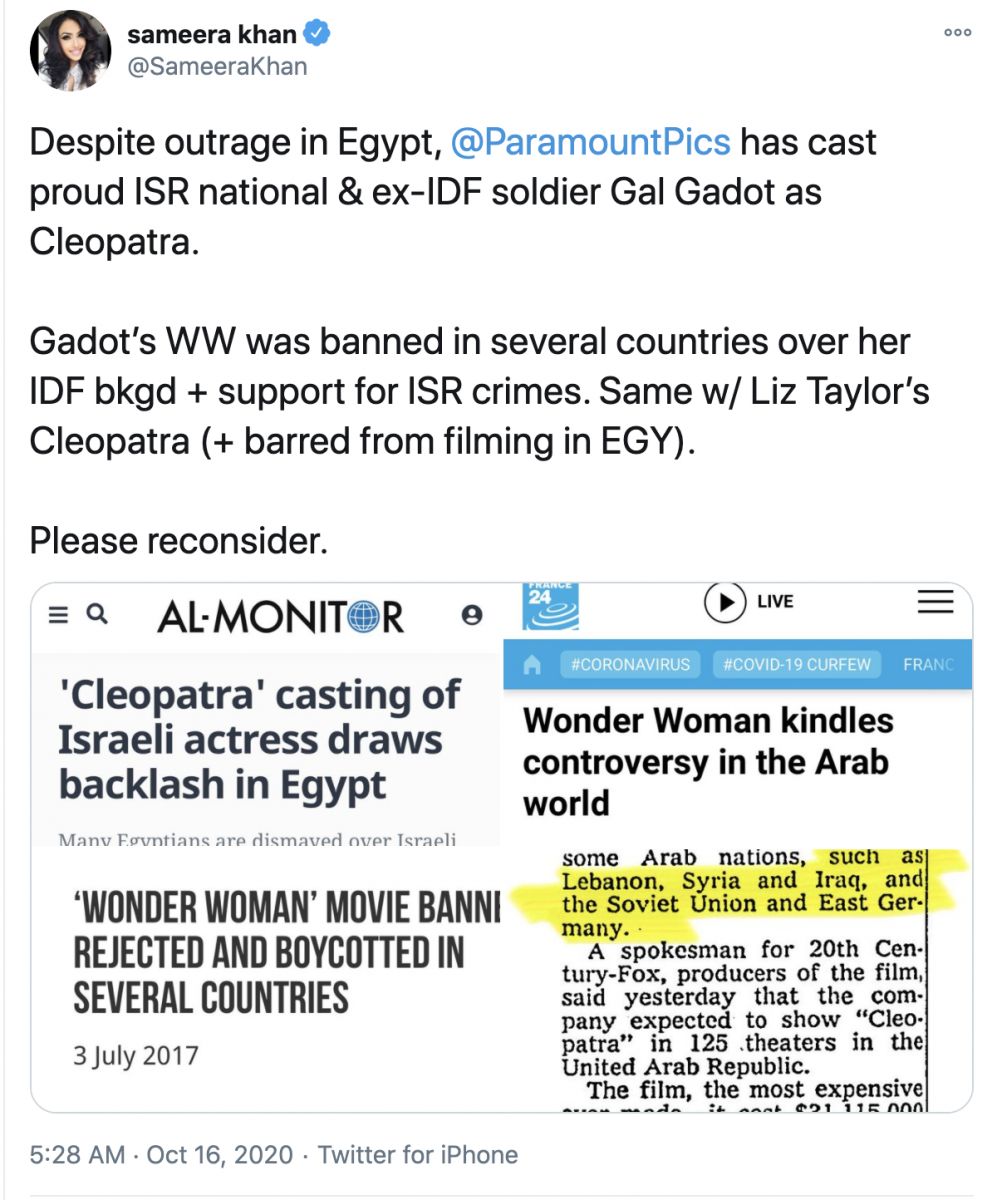

2. The implications of Gadot’s involvement for the normalization of the state of Israel’s policies in the Middle East and, thereby, the fate of Palestine:

Figure 4: Tweet by Sameera Khan, addressing the casting of Gadot as Cleopatra.

In this post, we, three ancient historians whose work focuses on issues of race and ethnicity, the Greek world, Egypt, and the colonial entanglements of Classics, offer some historically-anchored and geopolitically contextualized reflections on the significance of this new Hollywood production on Cleopatra. We also want to reflect on what the many, often culturally self-centered, reactions to this news teach us about the enduring, versatile appeal of the image of Cleopatra.

Whose voices, whose story?

When Kalogridis and Gadot tweet that they will bring “Cleopatra’s story” “to the big screen in a way she’s never been seen before” and that they will “tell her story for the first time through women's eyes,”, what does it actually mean?

While Gadot’s and Kalogridis’ social media posts foreground the feminist aspect of this project, their respective geopolitical positioning is crucial to understanding the genesis and actual significance of this new Hollywood version of Cleopatra VII’s life.

Kalogridis, whose family moved to Florida from Kalymnos in the early 20th c., has worked as a scriptwriter for many blockbusters. These include Oliver Stone’s 2004 movie Alexander, which has become somewhat infamous among many Classicists for its Eurocentric and Orientalist portrayal of Alexander as a ‘Greek’ civilizing hero (not to mention the bad script!). In a 2018 interview with The Hollywood Reporter, Kalogridis explains her love for stories featuring “strong women” to ancient Greek myths:

"When I was a kid, my grandparents were Greek immigrants on my father's side. My grandfather used to read me Greek myths, in which there are a great many goddesses and stories of strong women. And I was entranced by them. Then I started reading science fiction very young, and I loved it."

Kalogridis created a twitter account this October. Her profile picture is a head of Medusa, and her cover picture is a detail from a relief representing an Amazonomachy. At the time of writing this post, her only three tweets were dedicated to Cleopatra.

To write the script of Gadot’s Cleopatra seems to be a dream come true for Kalogridis. Indeed, when asked, in a 2010 Greek Reporter interview, whether she would like to work on another project linked to Greece besides Alexander, she said yes, and answered with her version of the “Classical Greece as foundation of the West” narrative:

"The truth of the matter is, all stories ultimately come back to Greek roots. I’m sorry but the basics of our mythological understanding of the world springs out of Aristotle, springs out of Greek culture, so everything I do is informed by that."

“Aristotle”? Not Homer? Setting that odd assertion aside, Kalogridis emphasized her Greek identity and stated that even her Shutter Island script was intended to have a Euripidian feel. For her, Cleopatra is as Greek a film as Alexander was.

As for Gadot’s involvement in the movie, it includes not only her starring in it, but, crucially, her stepping into the role of producer . Indeed, according to Deadline, the movie was her idea, and it was developed by her production company. Pilot Wave is a joint venture with her husband, real estate investor Jaron Varsano, in partnership with Jenkins, Charles Roven’s Atlas Entertainment, and Kalogridis, who laid out “the beats of an epic story that is based on the research she did after Gadot enlisted her.” The article also specifies that Kalogridis “will begin writing immediately, with Gadot, Jenkins, Roven and Varsano helping to shape a narrative.” Interviews with Gadot and her production partners make it clear that this is a dream role for her, and that she has substantial control over the shaping, writing, and execution of the project.

Because many of the social media comments and quickly-produced web articles focused so much on race and ethnicity, many commenters quickly framed critics of Gadot’s casting in Cleopatra as “antisemitic”. We should recall, however, that anti-semitism and criticism of a specific policy of the current Israeli government are not the same thing. To conflate them would be to label many Jewish Israelis themselves, particularly those in the political opposition, as antisemitic.

A closer look at criticisms of the casting, outside of the US in particular, suggests that the political issue has nothing to do with her Jewishness. Nor is it linked even to the fact that she is Israeli or has (like most Israelis) gone through military service. Rather, the issue is the dissonance between her performance of humanist feminism and her colonial, pro-occupation positioning. In other words, critics see a gap between what she has been publicly saying and the loudness of her silence regarding the treatment of Palestinians in occupied territories and Gaza. These entanglements are powerfully documented and discussed in an October 18 essay by Belen Frenandez and include her #IloveIDF facebook post of July 2014 written as Gaza was being bombed and hundreds of civilians (including women and children) killed, and her husband and business partner’s selling his hotel to a Russian tycoon who is known as the founder of illegal settlements.

Figure 5: Gal Gadot’s facebook post of July 25, 2014.

Gadot’s 2014 post hasn’t vanished from memories. Indeed, it may have contributed to the ban on Wonder Woman in many Arab countries in 2017. More recently, Jewish Voices for Peace’s summer 2020 tweet in response to Gadot’s ridiculed “Imagine” cover pointed to the hypocrisy of her performance (see here). Gadot is also a strong supporter of the Jewish National Fund, whose involvement in Palestinian dispossession and ethnic cleansing since 1948 has been well-documented (see also here).

But it was not just the 2014 post. In March 2019, Gadot supported her friend Rotem Sela’s criticism of Benjamin Netanyahu’s vision of an ethno-state of Israel (and thus of the treatment of Arab Israelis and non-white Jews in Israel as second rate citizens). Yet her (Hebrew) instagram post, which no doubt was carefully crafted so as not to alienate her fan base, is a masterpiece of spiritual by-passing that conveniently elides the question of the power imbalance between the “one another” she refers to.

What does it mean, therefore, for a movie addressing the life of Cleopatra, a figure viewed by Egyptians as an Egyptian icon and important part of their history, to be developed, produced, and acted by an Israeli woman who has a history of uncritically supporting the Israeli military? How might Gadot’s politics affect how this version of Cleopatra will be marketed? Likewise, how will Kalogridis’ ethnocentric understanding of the relationship between ancient Greekness and modern ‘Western’ culture and her claims to Cleopatra as not Egyptian impact her rendition of Cleopatra VII?

Ultimately, the debate centers over whether the framing of Gadot’s Cleopatra as a feminist empowerment story is a pernicious marketing strategy that (un)consciously, and perhaps conveniently, elides Gadot’s documented complicity with the military occupation of Palestine land and her support of Israel’s campaign for the normalization of this occupation (see notably on the matter here and here). The present movie project may be possible because the modern image of Cleopatra VII is rooted in the simplistic and misleading idea of her being a ‘Greek Macedonian queen of Egypt (and not an Egyptian queen). Or because it situates the ancient Cleopatra as a feminist embodiment of modern colonialist framework of ‘Western’ hegemonic power over the ‘Orient’. Or, because it presents Egyptian history while simultaneously excluding Egyptians and, by extension, Arab-speaking communities from the broader MENA world from the conversation. These layers of violence correspond to what Ann Laura Stoler calls colonial occlusion. They were articulated most clearly by Egyptian cartoonist Deena Mohamed and human rights attorney/Rutgers University professor Noura Erakat.

The dynamics described by Mohamed align with many archaeological and heritage works conducted in Israel. Just as State-supported archaeological work often aims at cementing Jewish autochthony and, thereby, erasing the region’s complex ancient history and invalidating modern Palestinian claims to the land, so too does a (white, ‘feminist’, Jewish and Christian) American-Israeli revision of the story of Cleopatra cement the whiteness of the queen while emphasizing its disconnection from both ancient and modern Egyptians. One really wonders what Edward Said would have said if he had read Gadot’s tweet.

It is obviously too soon to say anything about the Cleopatra movie itself. Yet it is fair to ask, as many Egyptians and others have begun, how Gadot’s and Kalogridis’ positioning as affluent, white women with eastern Mediterranean roots and commitments to imperial ideologies rooted in antiquity (American hegemony and the ‘Greek roots of Western civilization’ in the case of Kalogridis; Zionism and the military occupation of Palestinian land in the case of Gadot) has informed their commitment to this project.

All presentations of Cleopatra VII are a fantasy and Hollywood’s past attempts demonstrate a deep commitment to that fantasy as Orientalist. Further, in recent decades, it has become clear just how political these fantasies are--the debates over whether Cleopatra is ‘White’ or ‘Black’ coincide with controversy of the Whiteness or Blackness of ancient Egyptians and the colonial projects of anti-Blackness, Islamophobia, and the Israeli settlements in Palestine.

Greek, Egyptian, Black, White? The Modern Racial Politics of Cleopatra

One of the burning questions that always arises, and which was seen in evidence in the US and UK centered social media responses, is the question of the historical Cleopatra’s descent. This is, of course, a complicated question that has been engaged by many, many historians and pop culture enthusiasts. Indeed, most of the ‘first look’ media write-ups of the controversy fell very quickly into the old tropes of situating Gadot as Cleopatra within a longstanding “Was Cleopatra White?” vs. “Was Cleopatra Black?” skin color story, that has been raging since announcements years ago of a potential Angelina Jolie or Lady Gaga fronted version. Beyond this chromatic debate are the arguments over whether Cleopatra was an ‘African’ queen, Egyptian (but not ‘African’), or ‘Greek’ (i.e. Macedonian) queen, as if these are mutually exclusive and genetically unique identities. To debate this, scholars and the general public alike, look to the seemingly unexplainable gaps in Cleopatra’s family tree and retroject modern political identity categories backwards onto her.

The most prominent gaps are found in Cleopatra’s mother’s identity and her grandmother’s. In 2009, a group of BBC presenters/archaeologists proposed, based on analysis of a body claimed to be that of Arsinoe, Cleopatra’s sister, that their mother “had an ‘African’ skeleton.” It has also variously been argued that her paternal grandmother was indigenous Egyptian and so, potentially “Black”. Despite these attempts to understand the anomalies in Cleopatra’s family history, for the most part, when asked, most scholars and students of the Greco-Roman world, will say, without hesitation “Cleopatra VII was white—of Macedonian descent, as were all of the Ptolemy rulers, who lived in Egypt.” They often even dismiss the speculations that she may not be “White” as not credible.

The reality, however, is that “White” and “Black” are not ancient categories of race or ethnicity and “Egyptian”, “Macedonian”, “Greek” and “African” have different modern meanings and invoke different political and social affiliations than they did in antiquity. Even the qualification that Cleopatra was a “Macedonian Greek” echos the contemporary disputes over the use of the name “Macedonia”. Trying to decide into which of these identities Cleopatra fits is like putting a round peg into a square hole. More importantly, when scholars perpetuate the idea that her family tree defines her Greekness, Egyptianness, or Africanness, or even her ‘race’ at all, they perpetuate the idea that the modern racial identities we inhabit are universal across time and place. But Cleopatra does not have a ‘race’ as we understand it and to make any claims to being able to identify the “true racial background” of Cleopatra is to perpetuate a modern political position. She cannot be “at least 50% Egyptian” or “pure Macedonian Greek” because such things are modern socially and politically important and structured forms of identity; race is not a genetic truth. If we take our cue from antiquity itself, the ancient sources on Cleopatra are uninterested in disputing or even discussing her identity in the ways we obsess over.

Before we can talk about who Cleopatra was and who should play her on film or TV, then, we need to first be honest that any casting of Cleopatra is one that conforms to a modern political desire or social fantasy, whether that fantasy is of a White antiquity or a desire for inclusive representation in popular media. From this vantage point, it is much easier to understand why controversy erupts so frequently over Hollywood and television castings. We have competing visions of who Cleopatra is to us. The problem ultimately becomes who is ‘us’?

Figure 6: A late medieval conception of Cleopatra and Julius Caesar made in Avignon, France and now at the British Library (BL Eg 1500, f. 15v, 14th century CE) (Public Domain).

Authors