Dora Gao and Arum Park

January 9, 2022

Like many educators, I have found myself in an endless loop lately of thinking and rethinking my teaching principles and practices — a loop caused by the unprecedented teaching conditions the pandemic has brought upon us. Though I consider myself a thoughtful instructor, I admit that I have never thought so extensively, carefully, and critically about the purposes and desired outcomes of my teaching as I have in the months between March 2020 and now. Each week of each semester involves calibrating and recalibrating my courses, as I hope to meet the needs of my students and help them balance their lives within the classroom and without. I have become more attuned to the extramural realities that bear on my students’ learning, and as someone who works at a Hispanic-serving Institution, a desire for inclusivity increasingly informs the way I teach. My own institution just recently offered its first workshop on culturally responsive pedagogy, which provided me with many new tools for teaching in inclusive ways. Among other things, I realized that any kind of responsive pedagogy involves constant conversation with one’s colleagues, to generate, refresh, and fine-tune ways of teaching with a view toward inclusion and accessibility.

It was in this spirit that I happened to have a conversation about teaching with Dora Gao, a fellow officer of the Asian and Asian American Classical Caucus and an instructor devoted to inclusive and culturally sensitive teaching. We put some of our thoughts down in writing, in case they might benefit the readership of the SCS Blog.

Arum Park: What does it mean to be inclusive and/or culturally responsive in our teaching?

Dora Gao: For me, it means being considerate of the unique backgrounds and experiences that students might bring to the classroom and how this might affect their learning. Positionality is different for every student, which means that different students have different perspectives and priorities. Some may have experienced trauma — for varying reasons, of varying types, and to varying degrees. All of these are factors that will affect how they engage with the material we bring to them in our courses.

Being aware of and sensitive to these factors means acknowledging that teaching cannot be a one-size-fits-all approach. Granted, we cannot tailor a shared classroom to each individual student, so, in many cases, culturally responsive teaching requires prioritizing the experiences of the most marginalized students whose perspectives and experiences have not been centered in traditional teaching practices.

AP: Why do we need culturally responsive or inclusive teaching in Classics?

DG: Classics has a long history of inflicting material harm upon various populations. It has long been entwined with imperialism — which we cannot and should not divorce from the ancient texts, materials, and contexts themselves. Further, the ways we teach the ancient languages can subject students to incredibly harmful and oppressive ideologies. For instance, beginning textbooks often include narratives involving stock characters who are enslaved, or introduce vocabularies of violence without explaining the social context behind those words. Advanced students may read misogynistic, racist, ableist, or otherwise harmful content in ancient texts without ever stopping to process and discuss the presence of these references or jokes, because they have often been conditioned to focus on grammar and syntax rather than content. Teaching in an intentionally culturally responsive and responsible way is one way we can begin to rectify this damage and avoid inflicting new trauma upon our students.

AP: You have a recent example of how a culturally sensitive approach to your classroom enabled you to teach a difficult topic effectively and with care. Can you tell us the context and what happened?

DG: My current teaching assignment requires me to lead discussion sections for an introductory history course. One week, the topic of discussion was to be Macaulay’s Minute on Indian Education, a memorandum arguing that the British should educate Indian natives in only English and teach them English literature and history rather than their native languages of Arabic and Sanskrit. You can see how “Classics” becomes implicated in British imperialism and colonialism here, since Macaulay’s Minute documents a moment in which Indian antiquity — in the hands of a British imperialist —is relegated to a position inferior to Greco-Roman antiquity. Essentially, the study of antiquity excludes anything that undermines a British imperialist agenda, i.e., a native Indian classical heritage that demonstrates that the people Britain is colonizing have a long and rich cultural and intellectual history of their own.

This document is not only incredibly harmful in the rhetoric that it uses to describe Indians (as I’m sure you can imagine), but also in the way that it erases the many formidable literary and scientific accomplishments of India. Knowing that I had no choice but to expose my students to this rhetoric and keeping in mind that several of my students were students of color (and a few were Indian), I took the following approach:

- At the beginning of class, I asked everyone to do a 3-minute reflection on the reading and gave them space to process or at least acknowledge the affective impact of a document such as this. Significantly, I did the reflection too. I then let people share their thoughts, and I shared my own about how I was angered by the document, how I found it offensive, and even how I wondered whether being a historian would ever be enough to “rectify” the violence and horrors of imperialism. I tried to model for my students that “objectivity” and emotional disconnect were not necessary or even possible for historians. We are humans first and historians second.

- I then immediately acknowledged and made clear that this document was unequivocally racist, harmful, and imperialistic. The last thing I wanted was for anyone to justify British imperialism by arguing that bringing “culture and civilization” to other people was good.

- I also gave a content warning. I wanted to send a clear signal to the students that I cared about their well-being, and that it was perfectly acceptable and encouraged for them to take care of themselves through this difficult reading. Also, I always try to attach an action to my content warnings: not just “this lecture/reading/section features difficult content,” but also “please take care of yourselves — whether that means tuning out, closing your eyes, or even leaving the room — in whatever way you need.”

- I made it clear why we were reading this document, i.e., why I was giving any more exposure to this awful document. I made it clear that the only reason why we were engaging with this document was because we were looking to understand how the harmful rhetoric it espoused was implicated in wider rhetorics of power, so that we can better dismantle these power structures when we encounter them in the present.

- When it came to close reading for the document, I made sure to steer clear from the specific adjectives used to describe the Indians and instead focused on the logics of empire and imperialism. I’m not sure how well this worked, because all the rhetoric is awful, but I do think there’s a difference between abstract gestures to power and control and specific words used to denigrate groups of people.

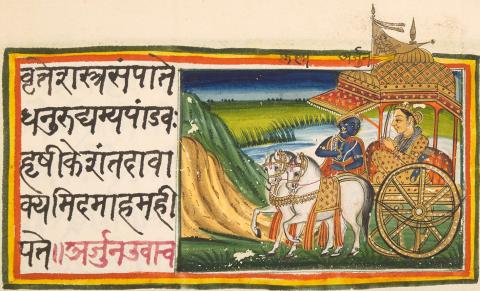

- There wasn’t much time to talk up the amazing accomplishments of South Asia, but I made sure to include this image of the Bhagavad Gita from the British Library, to illustrate exactly how British rhetoric was not only racist but also simply false (and to hopefully spark interest in Indian literature and culture among students).

I was really worried about one particular discussion section, but it ended up being one of my best, and I’m still seeing the results of that teaching moment as I grade their essays, in which they discuss with critical perceptiveness the ways in which Macaulay’s Minute is an example of how history and power are inexorably intertwined.

AP: There are so many inspiring things about the approach you outline here, but I want to draw attention in particular to your willingness to embed yourself in the students’ learning experience and share how your own positionality informed your reaction to the material. I think one of the potential difficulties of teaching inclusively is that it does require a certain vulnerability on the part of the instructor.

Maybe we can do a thought experiment — what would a non-inclusive or culturally unresponsive approach have looked like? And what would have happened from it?

DG: A culturally insensitive approach might have aimed for “objective analysis” (whatever that means) without recognizing that affective distance is a privilege that not every student or instructor possesses. Such an approach would have been dismissive of any pain or trauma response induced by something like Macaulay’s Minute, even though this document was expressly designed to inflict trauma. The traditional classroom and academy do not explicitly aim for inclusiveness and thus do not provide structures for supporting, understanding, or healing trauma that might occur in the context of academic activity. My greatest fear was that if I took too clinical an approach or put on a veneer of impartiality, a marginalized student might leave my classroom sad, hurt, or traumatized by the reading — and unsure how to process or deal with those feelings. I myself experienced this a lot as an undergrad, and even sometimes as a grad student. But I firmly believe that we are not worse scholars just because we intimately and instinctively react to harmful documents that were intended to provoke such reactions.

AP: One thing I love about this experience you’ve been describing is that this kind of approach to teaching requires a community of instructors. I remember the conversation in which you sought advice on how to teach this text. You came up with what turned out to be an effective and engaging approach in part by bouncing ideas off other instructors about what works, what doesn’t, what the pros and cons of various approaches might be. In other words, these kinds of teaching strategies don’t occur in a vacuum but are born of collaborative and supportive conversations among instructors who are aiming for similar goals — which I myself forget or take for granted sometimes.

DG: Yes, this is very important: this was a successful experience for me, but it was emotionally and mentally exhausting. My week was basically wrecked between worrying about one particular discussion section and the writing/rewriting of lesson plans. Ideally, every class and document could and should enjoy this sort of careful attention, but I don’t have the time and energy for this every week, especially when as a student myself, I am dealing with similar stressors. Having a support network of like-minded scholars can make teaching feel less isolating and help distribute labor and best practices.

AP: Thank you, Dora, for sharing your experience, from which I learned a lot. Your specific example occurred in the context of a history class, but your approach is applicable to any number of Classics classes too, especially the broad take-home message that culturally sensitive teaching requires us to be clear, intentional, and thoughtful about the content we teach and what we want our students to learn.

Header image: Illustrated page from the Bhagavad Gita. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Authors