Gabriel Moss

February 13, 2017

The Pompeii Bibliography and Mapping Project, directed by Eric Poehler, sets itself lofty goals. PBMP seeks to compile a comprehensive online bibliography and full-text archive of scholarly research on Pompeii, to construct a data-rich, interactive map of the ancient city, and to integrate both into a genre-bending “carto-bibliography” linking scholarly resources with the physical spaces they study. By its own admission (in a 2016 NEH White Paper), PBMP has not yet fully achieved these goals with the project’s first products, a Zotero bibliography and web-map published in late 2014. Some of the stumbling blocks this project faces (such as the scale of its data, legal obstacles, and the inflexibility of available software) will be all too familiar to practitioners of the digital humanities. Yet despite their flaws, these first fruits of the labors of Poehler, et al., provide a valuable digital research tool for students and scholars of ancient Pompeii, and promise to form the basis for improved future iterations.

Bibliography

The central problem which PBMP seeks to address is the scale and dispersal of scholarly work on Pompeii, which features several centuries’ worth of contributions spread among far-flung publications and archives. To this end, the project’s online bibliography is a largely successful contribution. Taking Laurentino García y García’s massive Nova Bibliotheca Pompeiana (1998) as its starting point, PBMP’s reference database has expanded to include over 1,800 entries. Built upon Zotero’s popular and user-friendly bibliographic software, the archive is searchable by title, author, and date of publication. Through immense effort (and no small amount of technical know-how) Poehler and his team have constructed a Pompeii bibliography of unparalleled scale; with proper upkeep, it may provide for Pompeii studies what L’Année philologique has long provided for the classics more broadly, and stand as an all-encompassing res gestae for work done on the ancient city.

That said, several issues limit the usability and sustainability of the PBMP bibliography. For instance, a Zotero database of this size is impossible to manually organize with subject tags, so it remains difficult to browse the bibliography by research topic and subject area. In addition, converting the bibliography into a full-text repository of Pompeiian research will face major legal challenges until publishers renounce copyright protection with the same gusto as the open data community. It is worth noting here, with some surprise, that PBMP itself is copyrighted material, and does not seem to be openly licensed under Creative Commons.

Finally, and most immediately, PBMP could do a better job explicating and standardizing the process by which new references are added to the Zotero bibliography. Looking back over PBMP’s progress, it is not particularly clear what criteria have been used in expanding the bibliography from García y García’s original. Looking forward, it is unclear how PBMP will take advantage of contributions from the broader community of Pompeii scholars. While Poehler and his team have requested references from their colleagues, there is not yet a structure to bring contributors into the fold of institutionalized membership and incentivize their work with authorship credit (such as the systems currently used by Pleiades, Pelagios, and others). Without such a structure for community contributions, the growth and sustainability of the PBMP bibliography threatens to be haphazard.

Web-Map

Like its bibliography, PBMP’s web-map is a promising (though not flawless) contribution to the field. The map draws upon a rich dataset of over 15,000 objects. In addition to objects representing the public and infrastructural architecture of Pompeii (streets, sidewalks, fountains, etc.) PBMP includes data-rich files of the properties within the city, following the Corpus Topographicum Pompeianum (1983) and Liselotte Eschebach’s Gebäudeverzeichnis und Stadtplan der antiken Stadt Pompeii (1993). PBMP’s dataset, which can be downloaded and manipulated using GIS software, promises to be one of the project’s most useful contributions to the study of Pompeii; other projects studying the physical space of the ancient city, such as Rebecca Benefiel et al.’s Ancient Graffiti Project, are already using PBMP’s data to support their work.

Underlying data aside, PBMP’s first web-map provides a striking visual depiction of ancient Pompeii. Published using ArcGIS Online, the map draws its many vector data files over a beautiful tile set showing an architectural plan of Pompeii’s excavated areas. The map does well to keep its masses of vector data from overwhelming the viewer; colors are generally muted and some layers are invisible by default. Clicking on features in the map map brings up additional information, such as bibliographic references and links to the relevant Pompeii in Pictures pages.

While the PBMP web-map is visually attractive and built on excellent data, its functionality is still somewhat restricted, in part by the constraints of the ArcGIS Online platform. Most importantly, the map is not easily searchable; users without a working knowledge of Pompeii may struggle to navigate. The PBMP team might consider shifting to a GIS platform custom-built for their purposes. While ArcGIS is relatively user-friendly, it may not prove flexible enough to meet this project’s more advanced requirements.

Conclusions

In isolation, PBMP’s bibliography and web-map are both strong works of scholarship. Regrettably, in their current iterations they do not yet come together into the carto-bibliographic resource the project envisions. With the exception of some references included with the Corpus Topographicum Pompeianum properties, features on the web-map do not yet link out to bibliographical references in Zotero. References in Zotero do not link back to the relevant features on the web-map. The ultimate goal of PBMP, to link scholarship and space, remains unfulfilled.

Poehler, et al., should not be judged too harshly for these shortcomings. Like all digital projects, theirs is a work in progress, and the PBMP team should be commended for releasing their resources when they were valuable enough to aid the scholarly community, even if they were not yet perfected. [pullquote]PBMP gives scholars all over the world easy access to a comprehensive bibliography on Pompeii, as well as spatial data on the ancient city.[/pullquote] While these two features have yet to come together as initially anticipated, Poehler and his team seem to be on the right track. If nothing else, PBMP deserves praise for its ambitious scope and scale, and for daring to imagine a radically different kind of digital research tool.

Metadata:

Title: Pompeii Bibliography and Mapping Project

Description: Online bibliography and web-map on Roman Pompeii, seeking to link scholarly references with the physical spaces of the city.

URL: digitalhumanities.umass.edu/pbmp/

Creator: Eric Poehler

Publisher: None

Place: University of Massachusetts Amherst

Collection Title: [none]

Date Created: 2013–2017

Date Accessed: January 15, 2017

Availability: Free

Rights: Copyright 2017 Pompeii Bibliography and Mapping Project

Classification: databases, digitization, linked open data, mapping, reference materials

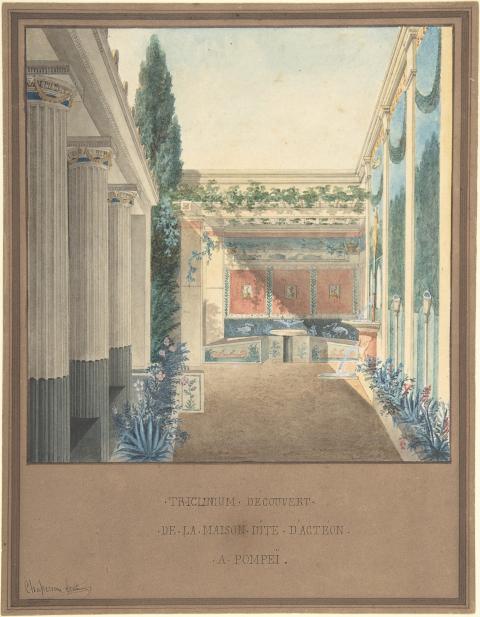

(Header Image: Triclinium, Excavated in the House of Actaeon, Pompeii. Charles Frédéric Chassériau, c. 1824. Accession Number 1975.131.95, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Licensed under CC0 1.0 Universal.)

Authors