Stephen Guerriero

November 15, 2021

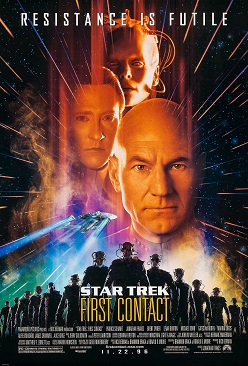

Growing up, one of my favorite shows was Star Trek: The Next Generation. At the risk of angering my fellow Trekkers, I am a Captain Picard guy all the way. In TNG and the subsequent movie, the concept of “First Contact” is a vitally important hinge point in human history. The term refers to the first time that one planetary civilization — in this case, humans — comes into contact with another, most famously the Vulcans. First Contact is something that is always meant to be planned, considered, and carefully done at precisely the right time. First Contact is also one of the guiding principles I follow as a middle school ancient history teacher. Instead of alien civilizations from space, I bring groups together across time, right here in my classroom — Ancient civilizations and modern 11-year-olds.

In my district, like most across the U.S., sixth grade is the first time students have ancient history as a standalone class. Most often in elementary schools, Social Studies are a small part of the curriculum compared with math, English, and STEM initiatives. Knowing this, I am aware of the great responsibility and privilege I have in introducing my students to the ancient world, its mythology, achievements, and the rise and fall of empires. My classroom is a place where I hope students capture some of the wonder and fascination that I have for the ancient Greeks, Nubians, Romans, Persians, Sumerians, and others that I teach them about. Lately, though, I have been even more careful in how exactly I want this “First Contact” to go.

Many historians and archaeologists developed, like me, a love of studying the ancient world in middle school, when we first picked up a copy of an old D’Aulaires’ paperback, or saw Indiana Jones, or were lucky enough to have had an amazing middle school history teacher ourselves. I still think so much of my 7th grade Latin teacher, Mr. Demerit, who taught every class like he was a great actor on stage. Unfortunately, middle school ancient history sometimes feels like an afterthought for professional organizations and for our colleagues in academia. What makes it frustrating is hearing that many higher education institutions are cutting back on their humanities departments generally, and their Classics, history, and archaeology departments specifically. One of the reasons often cited is low enrollment and the perception that student interest in studying the ancient world is waning. Meanwhile, “down” here at middle school, I see so many students fall in love with the stories of Mt. Olympus, or the Epic of Gilgamesh, and want to know so much more! What I want to encourage is a stronger connection between the scholarly work being done by my colleagues in academia and the kids in my middle school classroom.

That connection starts with applying new research, perspectives, and technology that develops in the field and in the literature to the K-12 level. Too often, our curricula lag far behind the current research, leading to the erasure of traditionally marginalized voices and a perpetuation of colonial historiography. In my twenty years of teaching, I have seen many positive changes in the way we teach about the ancient past, and these changes are accelerating even now. I am working in my district to modernize our curriculum in several ways to incorporate this new work, making my classroom a place where new developments in our field are reflected. My goal, to be sure, is to spark a love of learning about the ancient world in my students — but to do it with a diverse array of voices, making sure I convey the complexity, diversity, and legacy of those ancient cultures.

Figure 1: Movie poster for "Star Trek: First Contact." Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

One of the most important efforts is the recontextualization of Egypt as an African civilization, and the elevation of Nubia as a foundational civilization of the ancient world, not simply a trading outpost of Egypt. With the support of our Curriculum Coordinator, my Social Studies colleagues and I worked with Nubiologist Debora Heard to increase our department’s collective knowledge of ancient Nubia and how it was devalued, erased, and subject to racist downplay by archaeologists and historians of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. We were especially inspired by the blockbuster 2019–2020 Ancient Nubia Now exhibition at the Museum of Fine Arts (MFA), Boston.

By bravely confronting the racist conclusions of early 20th century archaeologists, including George Reisner, the MFA helped acknowledge that Nubia’s place in the ancient world should be as prominent and studied as that of Egypt or Rome. I hope that this effort helps give students a more accurate picture of how our modern conceptions of race have warped the traditional view of history we have received. We have partnered with the MFA to develop age-appropriate resources that address the bias of traditional archaeology and history to focus on who gets to tell the story, what is left out, who is not included, and how we can paint a fuller picture of our shared ancient past.

As part of our social studies department’s effort to recontextualize Egypt and Nubia as African, foundational civilizations, we have changed the way we frame these two civilizations. In the classroom, this means students will have equal amounts of time working with each culture. We are careful to give a more comprehensive view of Nubia beyond the “they traded with Egypt” trope that appears in many middle-school curricular materials. Specifically, we emphasize the advanced astronomical and seasonal functionality of the Nabta Playa lithic arrangements as markers of just how early Nubia begins to develop complex culture. I even had the chance to present this work to the Needham School Committee (start at 1:30:00) as a sample of our work with Debora Heard.

Figure 2: Lithic arrangements at Nabta Playa: The world’s oldest astronomical observatory. “P4260077c Nabta Playa, Western Desert, Egypt. 26th April 2006,” by Paul Ealing, 2011 (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The students also had an opportunity to respond to the MFA’s Ancient Nubia Now exhibit, which used primary sources to address systemic racism in archaeology and interpretations of ancient Nubia. In an assignment called “Ancient Nubia: Correcting the Record,” students read passages and watch video clips from the exhibit that address some of George Reisner’s attitudes about ancient Africa. Then, students are asked to explain why they think learning about ancient Nubia has historically been more difficult than learning about ancient Egypt, demonstrating their ability to make deep connections with nuance and sensitivity. Student Ahmira H., for example, wrote, “Learning about Nubia has been a difficult task. Prejudice and biased opinions took precedence over facts. Archeologists kept Nubia in the shadows while Egypt rose to the limelight.…In the words of Egyptologist Vanessa Davies, ‘So these early archeologists effectively made Egypt white.’…Egypt’s connections to Africa were removed and instead merged with the dominant Western culture.” Francesca A. noted, “I believe that if Reisner and other archaeologists during that time period had not had these views…there would be so much more to learn about Nubia.”

We have also partnered with Brandeis University to introduce our students to the Digital Humanities — a field not reflected in traditional middle-school curricular materials. This is especially important because K-12 materials often lag years behind new developments and discoveries at the professional and higher-education level, because of schools’ materials acquisition processes, teacher training, and the lack of quick turnaround from academic research to age-appropriate classroom resources that reflect new knowledge.

Figure 3: Helen Wong of the Brandeis Digital Humanities Lab speaks to 6th-grade students in Mr. Guerriero’s class about advances in laser scanning technology, 3D printing of artifacts, and object analysis in archaeological context.

This introduction to digital humanities means teaching kids about modern archaeological methods beyond trowel and brush (although they are part of it, too). We use digital imaging, 3D printing, AR/VR, GIS, and other cool technologies that archaeologists have incorporated into the field recently. The incorporation of digital technology and data science into ancient history classrooms means that we can better plan interdisciplinary units of study with our math and science colleagues. Lately, it seems that education has seen a competition over resources that favors STEM content areas at the expense of the humanities. Instead, programs that involve pedagogical methods both from social studies and from science and technology can benefit from both areas—and, subsequently, from better funding and resourcing.

Figure 4: Needham’s social studies teachers and technology integration specialists were treated to a firsthand look at the work being done in the Brandeis University Maker Lab, headed by Ian Roy. The teachers learned about the scope and advancement of the digital humanities as a field and collaborated to bring these lessons back into the classrooms of Needham’s middle and high school students.

Finally, we have identified certain areas of our curriculum that we should reexamine in terms of modern historiography and a better understanding of the bias underpinning the idea of “western” civilization and its privileged role in traditional curricula. One example: this school year, we will work with Dr. Kelly P. Dugan on reexamining the way we teach about enslaved people in ancient Greece and Rome — moving away from the “happy slave” narratives, and the attitude that ancient enslavement was somehow more palatable than race-based enslavement in the antebellum southern U.S.A. These misconceptions pervade many of our traditional curricular materials, and I hope our work is just as much about methodology of practice as it is about specific content. The way that we critically examine what we are teaching our students, and what materials we are using with them, can always benefit from an infusion of new ways of thinking, and of new voices that represent the diversity of the ancient world, along with the diversity of our modern scholarship.

More broadly, I want to emphasize just how important our focus on middle school teaching and learning of ancient history is for the future of our field. This affects how many students are inspired by, and want to continue studying about, the ancient past in future grades and at university. It is the first stage in determining how many students from marginalized groups — women, people of color, indigenous communities, LGTBTQ+ individuals, those with disability or neurodiversity — feel welcomed and represented in our study of the ancient past.

As a field, we who study and teach ancient history cannot afford to ignore what is happening in middle school and high school classrooms. We must find ways for the work of scholars to be reflected in our curricula without years of lag time. And most critically, we must address how we can reflect the attitudes of antiracism, inclusion, and interdisciplinary collaboration to our students from their first encounters with ancient history. Our great task at hand is to foster deeper cooperation and collaboration between academia and K-12 education to make “First Contact” meaningful, accurate, deeply inspiring, and the spark of a lifelong love of learning history. If we do not, then we risk middle school being both first contact and last.

Header image: Window display of Poseidon and books about ancient myth. Image courtesy of Stephen Guerriero.

Authors