T. H. M. Gellar-Goad

June 25, 2014

This month’s column is the first part in a series I’ll post every other month or so about how we can apply and see in action the 7 principles of research-based pedagogy described in the excellent book How Learning Works, by Susan Ambrose, et al. This month’s topic: knowledge organization, ch. 2 of the book.

Experts and novices mentally organize their knowledge in profoundly different ways. By and large, even when we as students or teachers explicitly discuss and consciously implement knowledge acquisition processes — like flashcards, or declension drills — our mental systems of organizing the knowledge acquired are generally implicit and subconscious. But the difference between expert and novice knowledge organizations has substantial consequences for effective ancient-language instruction.

Experts and novices mentally organize their knowledge in profoundly different ways. By and large, even when we as students or teachers explicitly discuss and consciously implement knowledge acquisition processes — like flashcards, or declension drills — our mental systems of organizing the knowledge acquired are generally implicit and subconscious. But the difference between expert and novice knowledge organizations has substantial consequences for effective ancient-language instruction.

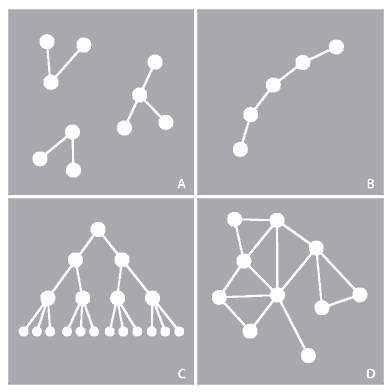

Novices tend to organize knowledge linearly: item A connects to item B connects to item C, so getting from A to C means going through B. In very early stages of studying a new subject, novices might not have formed any meaningful connections at all, but instead may have collected information into a cloud of seemingly unrelated points or tidbits. Experts, on the other hand, organize their knowledge in hierarchies or webs. (The image to the right, reproduced from How Learning Works (Figure 2.2, p. 50), visualizes these organizational methods, with A and B representing typical organizational structures of novices, and C and D those of experts). The expert structures offer more connections, richer connections, and more efficient access of knowledge — and they also explain why academics tend to go on “tangents,” because one piece of information leads not to one linear progression but to many interconnected ideas.

As a result, Latin or Greek teachers relate to the words, texts, topics, and themes that they teach much differently from how our students do. For example: my knowledge of Latin noun cases, ablative usages, prepositions, and vocabulary has been spun into a heavily-networked web through years of training and practice, while beginning and intermediate Latin students will at best generally organize this knowledge into a step-by-step path from the word to the meaning.

So when confronted with a sentence like bello Peloponnesio huius consilio atque auctoritate Athenienses bellum Syracusanis indixerunt (“in the Peloponnesian War, on his advice and authority, the Athenians declared war against the Syracusans,” Nepos Life of Alcibiades 3), a novice Latin learner must do the following, often in this order, for each word separately:

- find the portion of the word that constitutes the grammatical ending

- figure out whether that ending is for a noun, verb, or another part of speech

- figure out which declension/conjugation the noun/verb is

- figure out which particular case/verb ending is used in the word

- figure out what the word means by consulting a dictionary (possibly before step 1)

- if a noun, identify the case usage; if a verb, identify subjects and objects

And then s/he must go on to integrate these discrete investigations into a unified comprehension of the phrase.

Experienced readers of Latin, however, have many more approaches open to them, and are able to move through these approaches with greater speed and more automaticity than novices. My Latin vocabulary is organized into several hierarchies — so that my mind associates the noun auctoritas with categories like nouns, third-declension nouns, feminine nouns, nouns formed from verbs, abstract nouns, potentially metaliterary words, and political words. Such hierarchies aid me in simultaneously (rather than sequentially) accessing the information I need to identify auctoritate as a feminine ablative singular third-declension noun meaning “with/by authority/authorship/initiative” and to relate it to the rest of the phrase. And my knowledge of morphology and syntax is organized on multiple tracks, so that I can see auctoritate and bello at once as alike in being ablative and not alike in being different ablative uses. Finally, where a beginner’s handling of auctoritas will be limited to cycling through English translations offered by a dictionary or glossary, my understanding of the noun will be situated somewhere along the range of meanings it takes based on context within a passage, on genre, on period, and so forth.

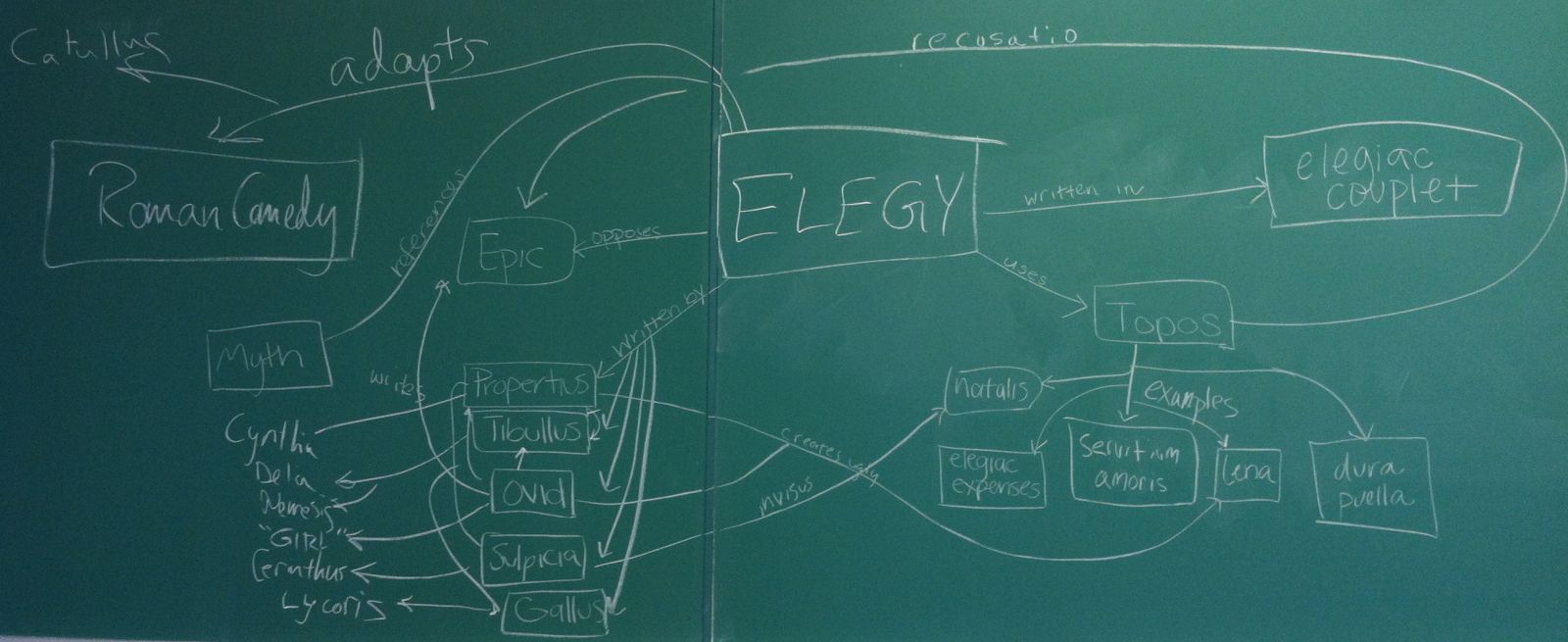

What, then, are some techniques we can use to help students enrich their connections and make their organizational systems more complex? The methods recommended in How Learning Works are nicely straightforward, and I’m certain they or variants are already in widespread use, particularly in secondary education. When introducing or assigning new morphology or vocabulary, for instance, we could use “advance organizers,” which offer students principles for a cognitive structure — prompting learners to group words not alphabetically but, say, by part of speech and a second time by thematic category. Syntactical rules and relationships could be delineated on concept maps, an extremely effective tool (albeit one often deprecated by students) whereby content items are linked to each other hierarchically and with meaningful connections (i.e., labeled or described). Concept maps are useful for enriching knowledge structures at higher conceptual level, as well: the photo below is of a concept map of the genre of Roman erotic elegy made by my advanced Latin students at the end of a fall 2012 elegy course at Wake Forest University.

In other words — and this will be an almost constant refrain throughout this “How learning work in the Greek in Latin classroom” series — the key to turning novice knowledge-organization systems into expert ones is to present the psychological principle of how learning works, to offer examples of expertise, and to induce students to practice expert modes of knowledge acquisition.