Young Kim

January 10, 2019

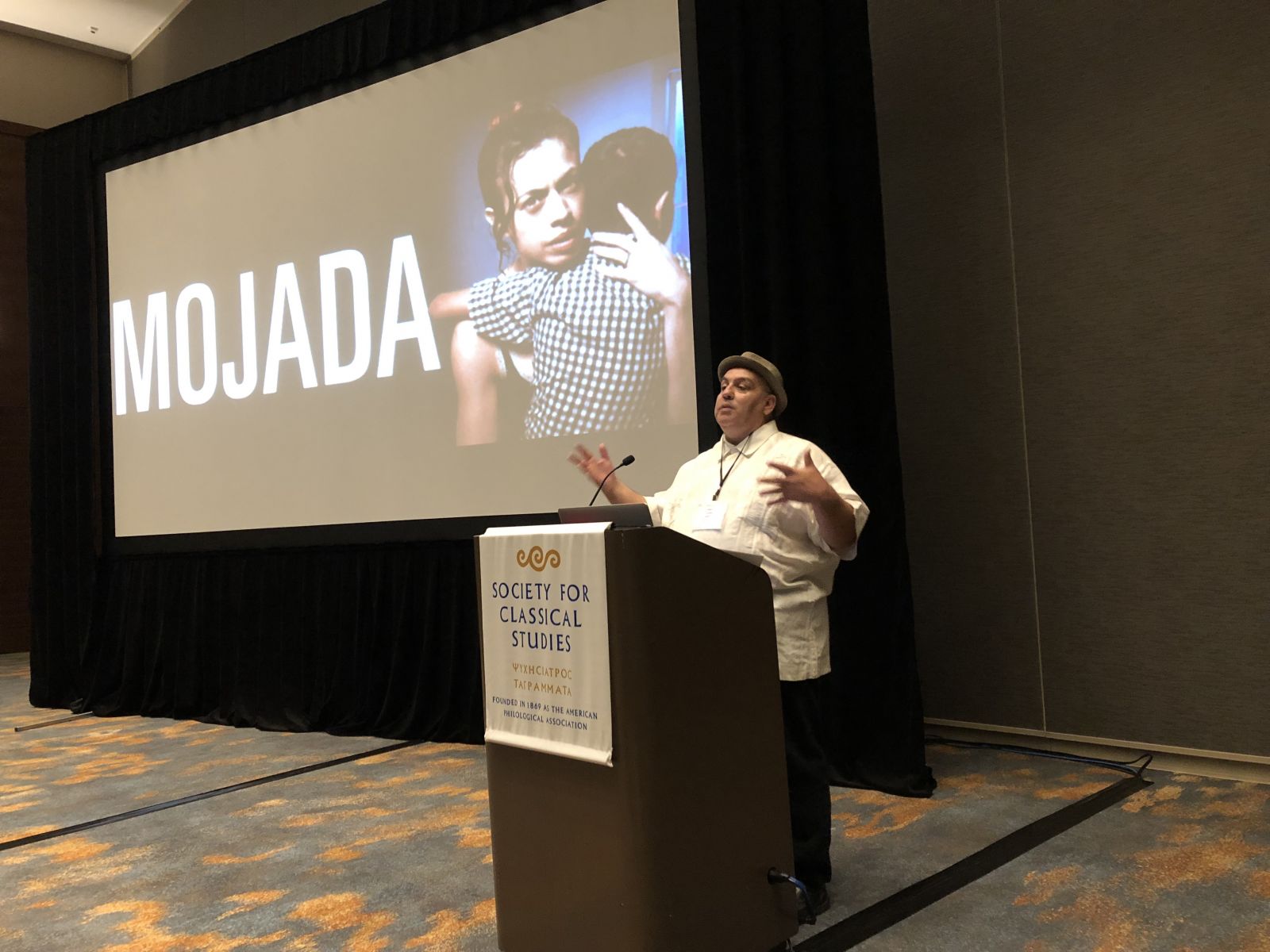

On Thursday evening at the annual meeting of the SCS, together with about 150 others, I witnessed, experienced, and participated in something beautiful. With the enthusiastic support of the SCS, Classics and Social Justice, and the organization I work for, the Onassis Foundation USA, playwright and activist Luis Alfaro shared with a captivated audience his heart, his brilliance, and his creativity, a shining example of the good that can be done with and to Classics, and the reach our discipline can have to new, perhaps unexpected audiences. I resist here the urge to discuss some of the painful ugliness we saw at our meeting, leaving only a hint of it in the title I originally thought of for this piece, because I do not want to take away from the light Luis brought to us.

The idea for this event initially came from Nancy Rabinowitz and Mary Louise Hart, with additional planning by Melinda Powers, all of whom know Luis’s work, especially what he has done with Greek tragedy on the contemporary stage. At the center of our thinking was the question of how to bring greater diversity to Classics, and there is no better example than Luis, who has adapted familiar works like Oedipus the King, Elektra, and Medea and presented them to audiences across the country. His professional profile lists the many venues—schools, civic playhouses, festivals, world-class theaters—in which his works have been produced, so I won’t repeat them here. But for those who do not know what he does in his Oedipus el Rey, Bruja, Electricidad, and Mojada, in essence Luis reimagines Greek tragedies and situates them in contemporary, gritty, urban settings, especially east Los Angeles, populated by characters inspired by his Chicano upbringing. As Classicists, we know well the themes of the original plays—fate and choice, justice, violence and revenge, the marginalization of the “other”—and Luis incisively works with these in his own interpretations, breathing intertextual life into the ancient, as he offers his own vision of the dramas in the present, exploring sexuality, gender, queerness, race and racism, immigration, gang culture, religion and ritual, and ultimately...love.

Imagine with me for a moment, how we as teachers of these texts, together with our students, might read and meditate on the ancient iterations alongside Luis’s. How could such a pedagogical practice invite and inspire a new generation of readers? Can we create a space wherein someone, for whom these very texts embody in verbal form a painful and oppressive colonial legacy, might participate in their subversion and conversion? And what if we saw these plays on the stage as part of our teaching? Too often we regard the arts as separate from the work we do as scholars and teachers, but I believe the vitality (and future) of our field absolutely depends on a more robust engagement with performance and performers. The arts must move to the center of our pedagogy.

Among the many features of Luis’s talk that inspired me was his approach to writing and producing theater, his methodology, as it were. He commits to living in the communities where his plays are produced, sometimes for over a year, such that his work organically take on aspects of the local community in the set design, actors, costumes, and even language. Luis also reflected on the idea that he does not imagine that he brings the “Classics” to the community, a notion we often think is the way to engender a love for them, dare I say by imposing a canon of texts in fixed translation and a particular hermeneutic for reading them. Rather, he brings his community to the Classics and allows his audiences to engage with the stories with their own idioms, ideas, and imaginations. In a fascinating panel that took place the next morning, Nancy, Mary, Amy Richlin, Tom Hawkins, Rosa Andújar, Jessica Kubzansky, and Melinda, each offered reflections on the impact of Luis’s work, especially at the intersection of social justice. Indeed, Luis himself believes, and rightly so, that his work is social change.

Luis Alfaro is not trained as a “Classicist” (whatever the parameters may be that we think define one as such) but in a very real way, he is more a Classicist than even the most learned and certified among us. Does he not fulfill the mission of the SCS, of “advancing knowledge, understanding, and appreciation of the ancient Greek and Roman world and its enduring value”? He is doing the work that we need to do to move the field into more diverse, more inclusive, and more hospitable directions. In my view, this is the hope for the future. Our guild must not just be open to hearing (once a year) from a Classicist, artist, and activist like Luis in our annual gatherings. Let us find them, invite them to our campuses, embrace their work, and perhaps most of all, listen to and learn from them, with humility.

Our ongoing discussions about bringing diversity to Classics cannot only be about importing persons of color into the field (H/T to Dan-el Padilla Peralta for teaching me this). We must initiate systemic changes, including, I believe, the scholarly and pedagogical lenses through which we read and interpret our sources and construct the narratives of the peoples of the past. In other words, we need to recognize that those from diverse and underrepresented backgrounds not only enrich our field by virtue of their presence, but their very being, their ousia, brings to our scholarship and teaching perspectives and approaches that cannot help but transform for the better our shared project of humanistic inquiry. This is what Luis brought to us, even for a brief moment. May there be many more.

Header Image: Athena looks on as Oedipus slays the Sphinx (Attic red-figured lekythos, 420-400 BCE now at the British Museum).

Authors