hmcelroy

June 14, 2021

LatinOCR and Rescribe are related optical character recognition (OCR) tools that substantially accelerate the conversion of scanned Latin to Unicode text and, in the case of Rescribe, to searchable PDF format. Both are pleasant to use but require a degree of comfort with command-line tools, at least to get up and running. Both use the Tesseract OCR engine, run on Windows, OS X, and Linux platforms, and are available open-source and free under the Apache License 2.0 through Rescribe Ltd., a nonprofit company founded by the developers, Nick White and Antonia Karaisl. The development was supported by a grant from the European Research Council and was based on research carried out at Durham University.

I discovered LatinOCR in the summer of 2020, after I had hand-transcribed the first five books of Martin Kraus’ Latin epitome of Heliodorus’ Aethiopica to read with students. It was a very laborious and time-consuming process, and I hoped to speed up the preparation of the second half of the text for the following year’s class. The native OCR in my installation of Adobe Acrobat Professional 8 does not support Latin, and the results of setting the language to Italian or Spanish produced near-total nonsense. Furthermore, Acrobat was wholly unequipped to deal with ligatures, unusual printing symbols, and early modern abbreviations. I discovered that one of the libraries that had a high-quality scan of the book offered free OCR services, and so I put in an OCR request, hoping their technology would do a better job than mine. The results were even worse than what Acrobat had given me. I went searching for Latin-specific OCR and was delighted to discover that LatinOCR was developed specifically for printed texts of the period when Kraus’ epitome was published. After a few challenges installing it and getting it to work, I ran a few test pages of Kraus’ text through it. The results, though imperfect, were very encouraging.

LatinOCR is specifically designed “to convert scans of early modern Latin printed text into Unicode text and PDF files that can be easily searched, copied, archived, and transformed” (LatinOCR website). It uses a training data set calibrated to handle the typefaces used in printing between 1500 and 1800 CE. As such, it can recognize ligatures, abbreviations, alternative letter forms, and other period signs (e.g., Æ Œ ſ ß † ‡ ÷ ※ ff fi fl ffi ffl ſt st), as well as standard letters and numbers.

Depending on the user’s operating system, Latin OCR can be deployed through different software (the recommended software and a guide to installation is given in the LatinOCR installation instructions for each platform). On OS X, the user first installs Homebrew, through which they install Tesseract. They then download the training data for Latin and install VietOCR (a graphical user interface originally developed for Vietnamese but useful for a number of languages). Once VietOCR is installed and configured according to the instructions, the user can process files directly in the interface or set a “watch folder.” Compatible files placed in the watch folder are automatically processed by the software, and VietOCR delivers the output to another folder designated by the user.

LatinOCR recommends preprocessing the files a bit before running the OCR on them. For example, if you start with a color PDF, you must export the pages as image files (VietOCR supports several file formats, and I have used TIFF, JPEG, and PNG originals with no discernible difference in the quality of the output) and should convert them to grayscale. LatinOCR recommends using a third-party tool such as ScanTailor to deskew (rotate to compensate for skewing of an image in the scanning process), despeckle (remove extraneous marks and non-text data from the scanned image), and binarize (convert from grayscale or color to black and white) the files before processing. Some of these functions are also available within VietOCR and may be available on the equivalent Linux and Windows applications. I have found that deskewing the images improves accuracy, as scanned documents from libraries, Google Books, and other online sources often have inconsistently aligned pages. Overaggressive despeckling can reduce the accuracy of the OCR, depending on the quality of the scan and the condition of the original pages.

Unsurprisingly, LatinOCR works best when processing cleanly printed text with few irregularities. It recognizes characters with about 99% accuracy on the most cleanly printed texts. To quantify accuracy in the following examples, I took a passage of at least 100 words and counted how many times the software misidentified a character, added or omitted a character, or failed to preserve the intended spacing of words — although, given the inconsistencies of spacing in early typesetting, some of its mistakes here are quite forgivable. I divided this by the total number of words in the passage. This should give would-be users a sense of how much human correction would be needed on a given text.

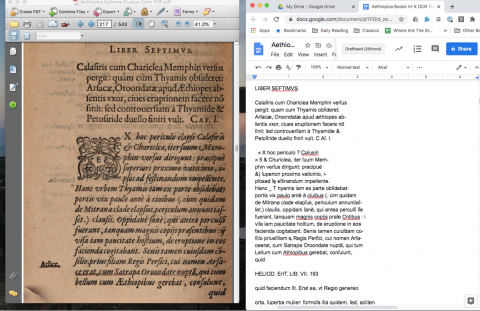

Figure 1: A page from Martin Kraus’ Aethiopica Epitome processed using LatinOCR within VietOCR. It handles the opening chapter summary well but is only 88% accurate with the italicized body text.

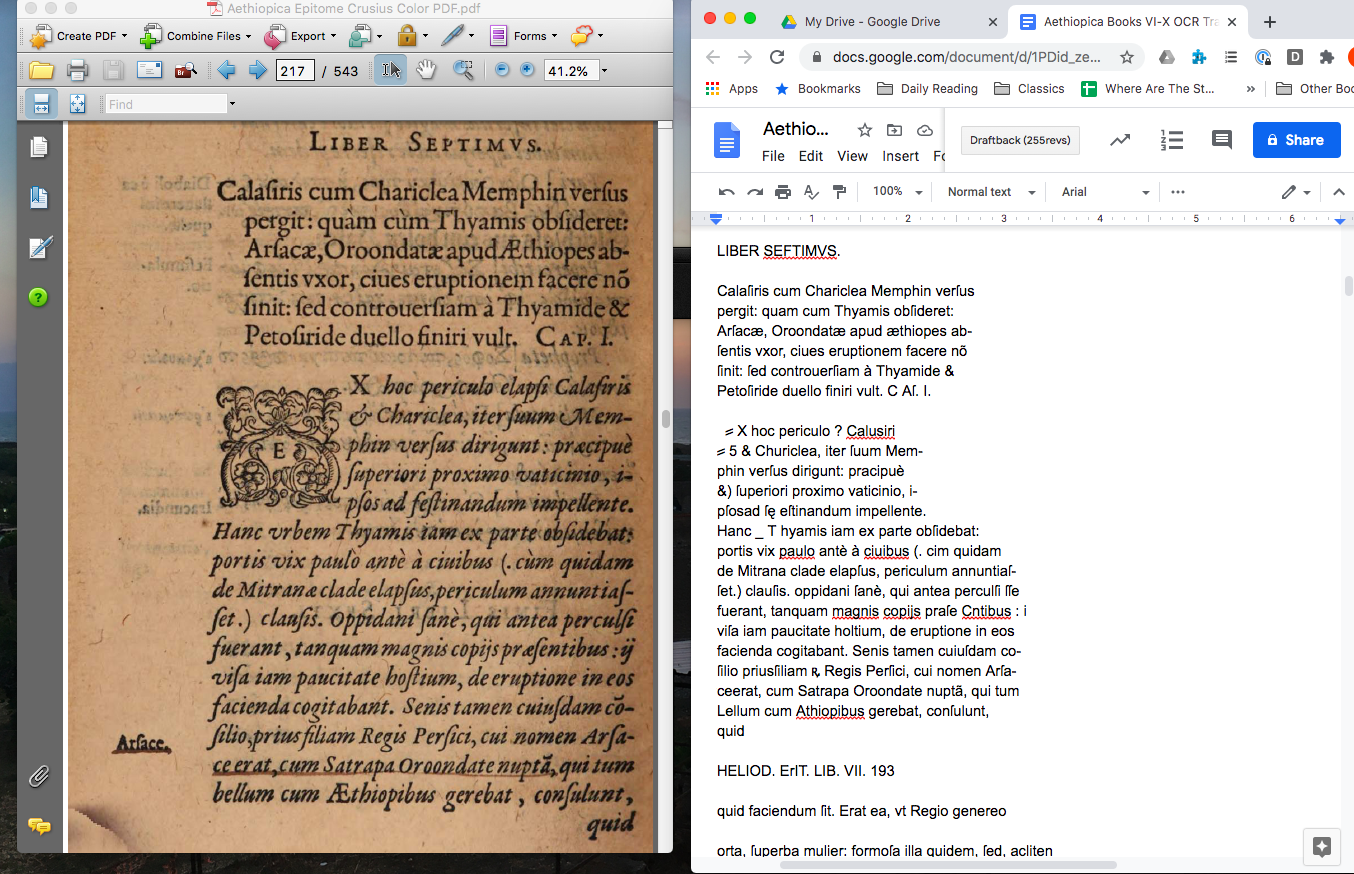

Figure 2: A page from Leo Africanus, De viris quibusdam illustribus apud Arabes and output from Latin OCR via VietOCR. It has some trouble with spacing (ductumiri in line 4 for ductum iri) but, given the variation in kerning in the original, this is often understandable. It also misreads hunc in line 4 as hune, but overall achieves approximately 97% accuracy.

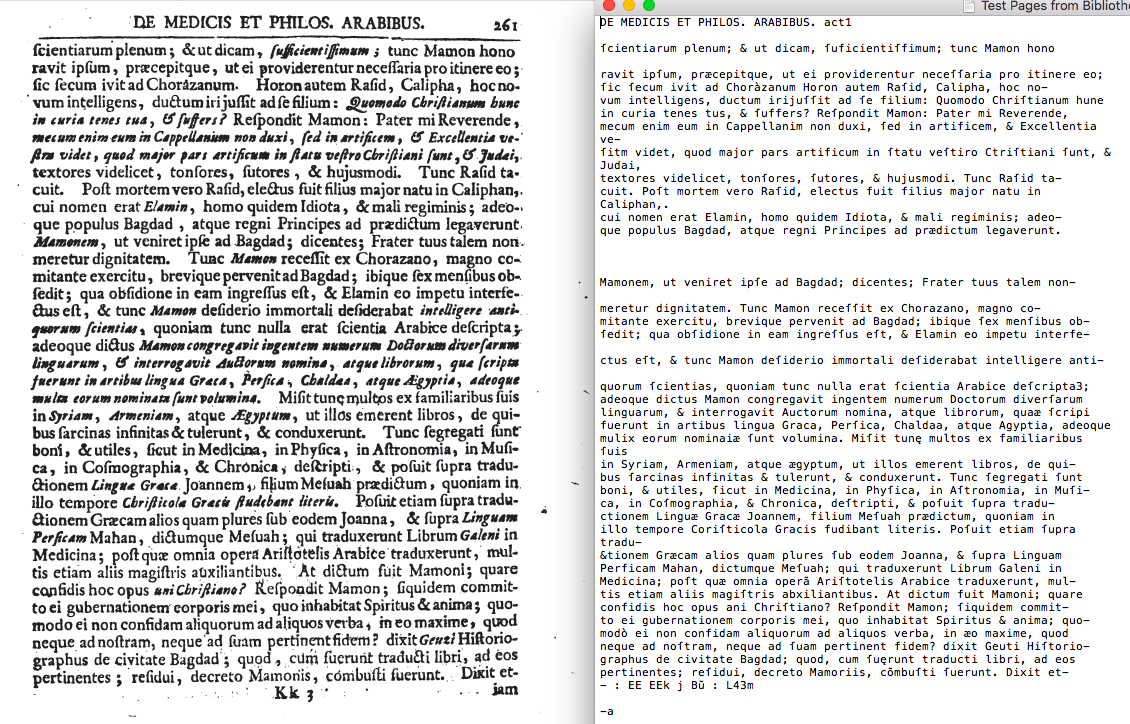

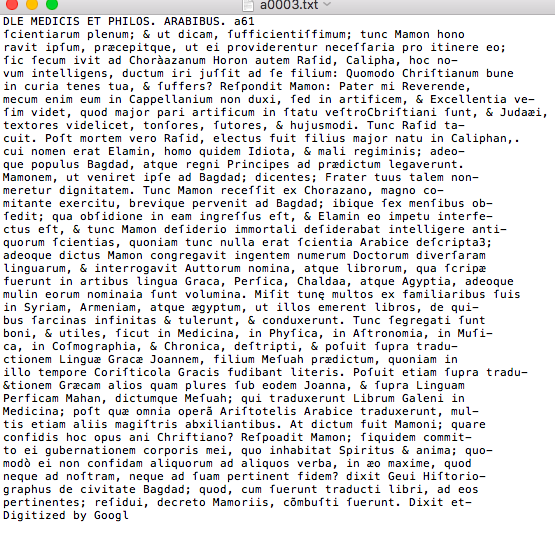

Figure 3: A page from Leo Africanus, De viris quibusdam illustribus apud Arabes as processed by Rescribe. It catches the space between ductum and iri in line 4 that LatinOCR missed, but gets more characters wrong or adds extra ones, resulting in closer to 96% accuracy.

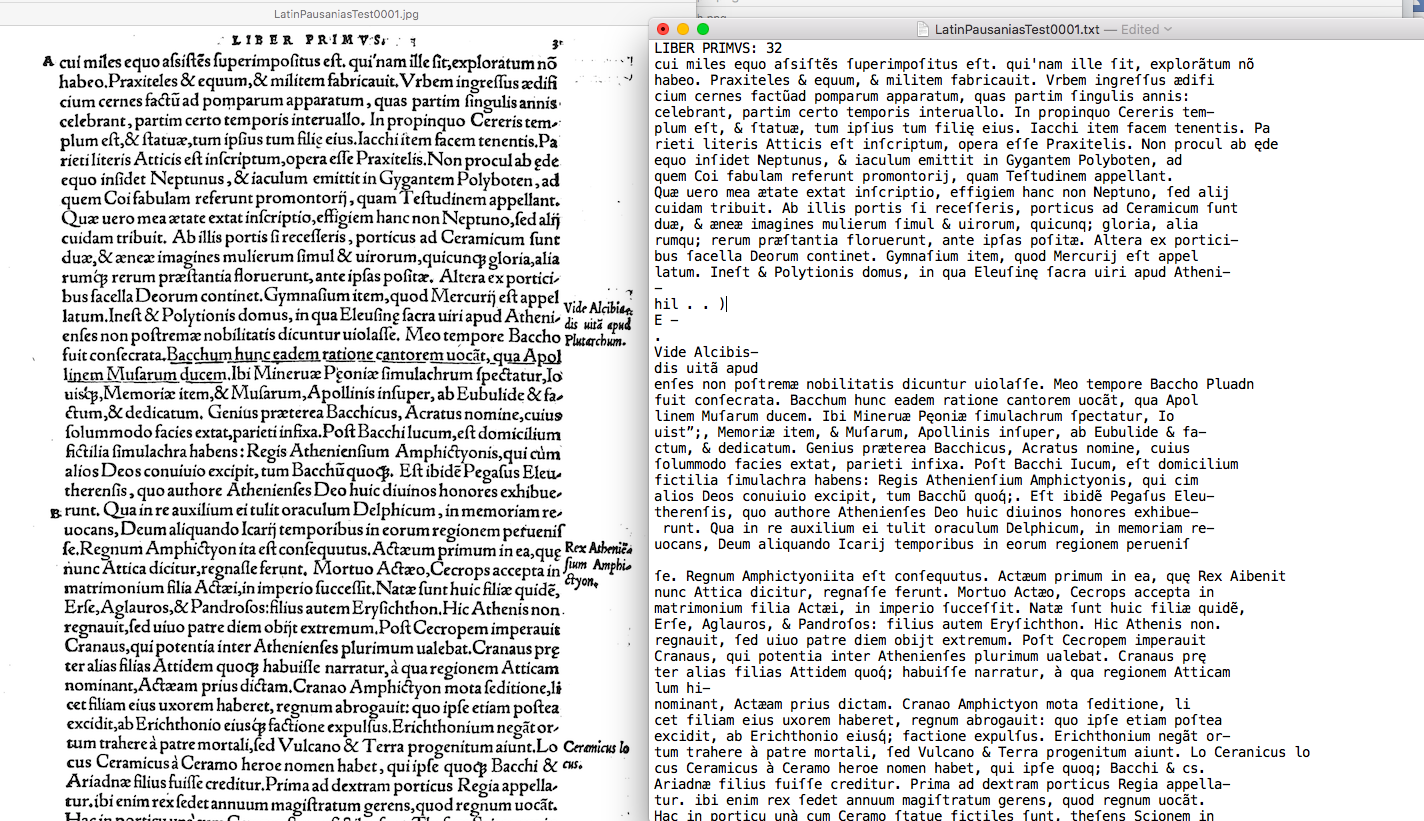

Figure 4: Abraham Loescher’s 1550 Latin Translation of Pausanias and output from Rescribe. The tool has regular challenges with the printed abbreviation for –que and doesn’t quite know what to do with text in the margins. However, it achieves approximately 99% accuracy and handles the period printing conventions very well.

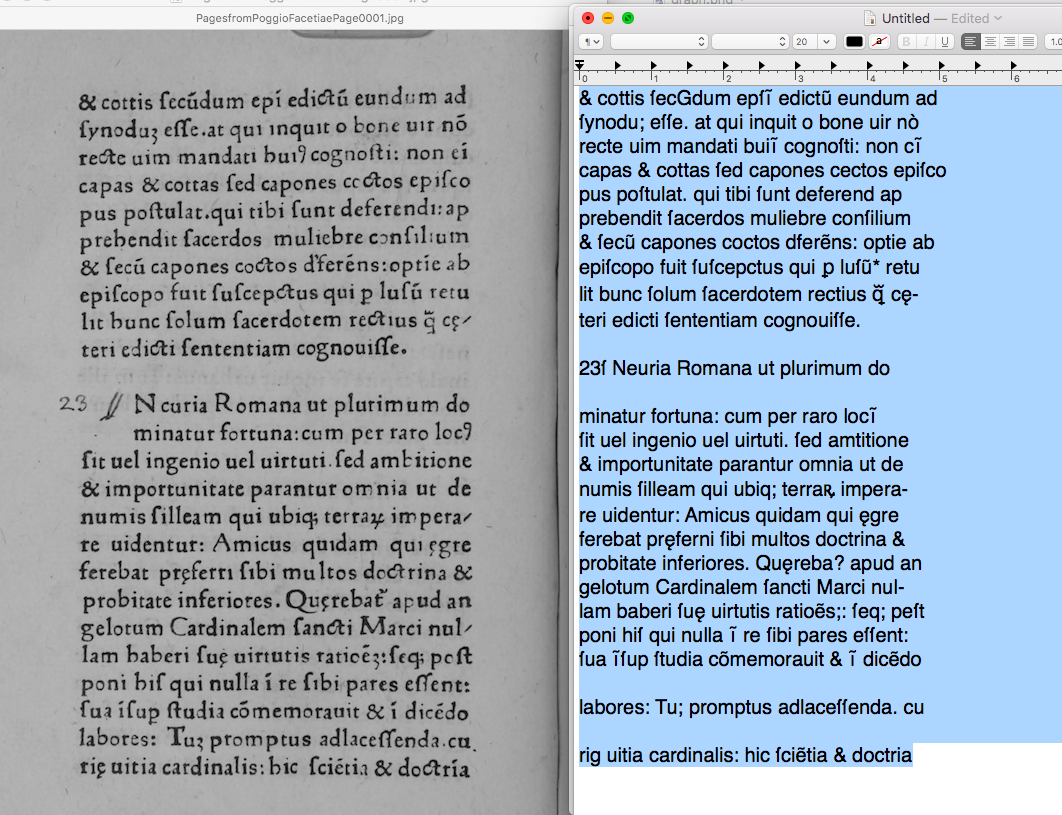

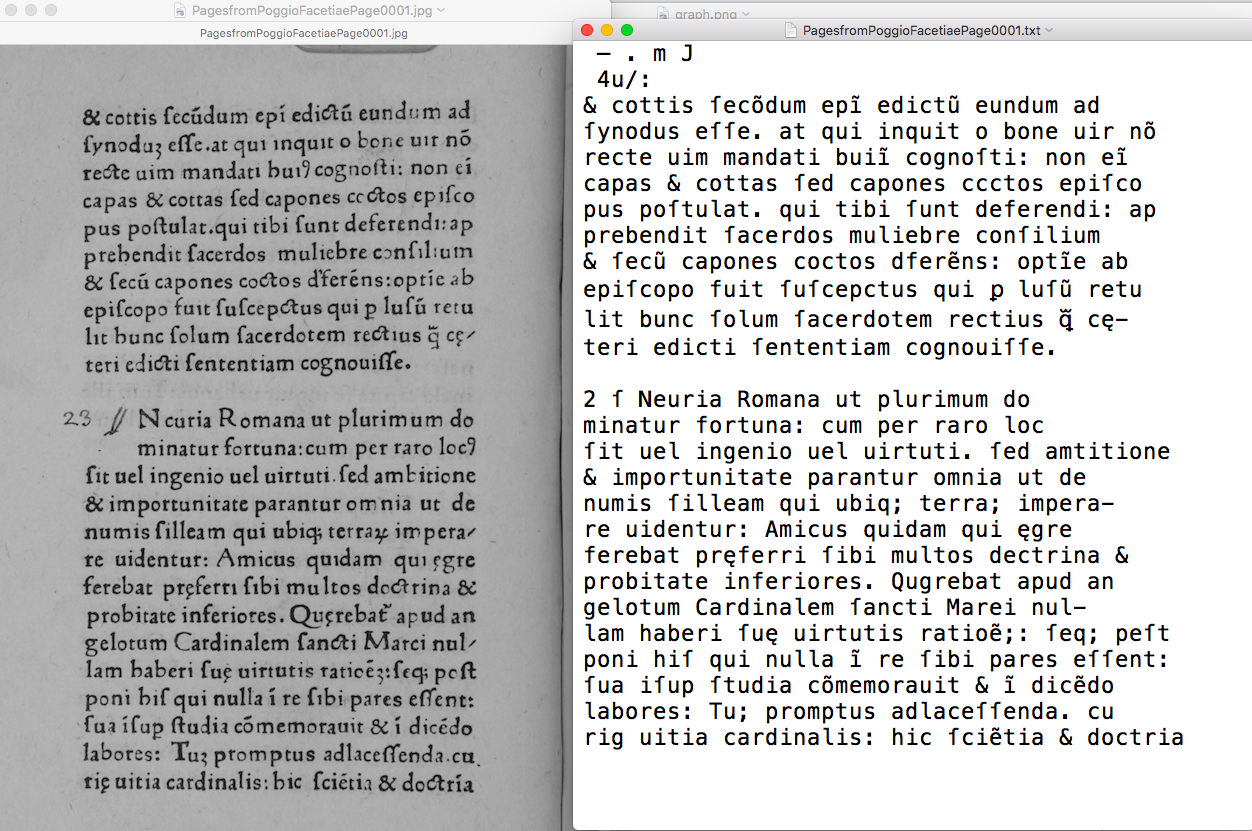

Figure 5: These tools still do fairly well on texts from outside the 1500–1800CE range for which they were developed. LatinOCR processed this 1471 edition of Poggio’s Facetiae (with handwritten headings and initials) with 83% accuracy.

Figure 6: Rescribe processed the same text with 85% accuracy.

LatinOCR struggles a bit with texts in italic typefaces, texts written with other languages interspersed among the Latin, and texts with marginal notes. These require more intensive human correction to yield readable results. The accuracy here is still impressive, at around 90%. As I mentioned, even the initial output is substantially more accurate than what I have received from some libraries that offer OCR service for their holdings.

In November 2020, the developers of LatinOCR released Rescribe. Rescribe is a desktop version of the more comprehensive pipeline of server-based tools (preprocessing, OCR, post-processing analysis) they use to perform OCR on larger collections and corpora. It runs in the command-line environment of the user’s computer. It does some of the necessary binarization and preprocessing before the OCR process, making for a more streamlined workflow than that of LatinOCR. It takes less than one minute per page to perform the whole process. As part of the run command, the user designates the folder containing the image files in the command line and the tool returns multiple outputs to that folder. These outputs include:

- a searchable PDF of the original text;

- plain text files for each page processed;

- a graph indicating the confidence of the OCR accuracy over all pages of the text;

- a file indicating the confidence of OCR accuracy for each page; and

- an hOCR directory (one of the open source standards for data obtained from OCR).

For some users, including me, running software from a command-line prompt is a trip down memory lane, while for others, it will be an entirely new experience. Fortunately, the necessary command syntax is fairly straightforward and most of it can be pasted in from elsewhere until it becomes second nature.

The quality of output from Rescribe is similar to that of Latin OCR. Because of the built-in preprocessing, the turnaround time is a bit longer. Depending on the original document, I often find one tool gives me slightly better results than the other. I recommend processing one or more test pages through each tool to see which gives the most accurate output. Rescribe also has training data available for Greek and Carolingian Minuscule. I have not used either of these, but their existence is exciting.

Neither tool handles initial letters with decoration well, but this requires only minor intervention on the user’s part. The print-type and quality of the original also affect how coherently they render text printed in the margins. Rescribe is a bit finicky about the filename format, but this is a small obstacle. If it encounters an incompatible file in the folder being processed, it will not process anything. Hidden files (such as .DS_Store), which are often created automatically, can be a real nuisance, so it pays to find them with a directory search that shows hidden files and then remove them before processing (the command ls -a reveals hidden files in the directory, and the command rm [filename] removes them).

Both tools save time and labor when converting scanned Latin text to Unicode. For Windows and OS X users, LatinOCR only requires an up-front foray into command-line tools, after which the graphical user interface (GUI) and watch folder make processing quite straightforward. The installation of the Rescribe desktop tool has fewer steps, and the inclusion of preprocessing makes for a streamlined process but requires returning to the command line environment (and likely reformatting image file names) every time you wish to process a document. While I use both, I’d recommend Rescribe for those who are more comfortable getting under the hood of their operating systems and working with command-line tools. For those less inclined to work in the command-line environment, LatinOCR’s more straightforward GUI is probably the better choice.

Used in conjunction with other digital classics tools like The Bridge Lemmatizer, Latin OCR and Rescribe enable fairly rapid creation of useful digital editions of the wide array of Latin texts that have been digitized but lack searchable, manipulatable digital texts. This possibility creates an opportunity to widen the range of Latin authors students and scholars can read. For example, the substantial body of scanned neo-Latin texts available online provides an opportunity to bring more women authors into our curricula. Neo-Latin texts written in or describing the Americas, Asia, and Africa can also expand the geographical range of our reading and scholarship. For those of us eager to expand the reach and scope of our field, these tools are an immensely welcome addition to our repertoire.

Metadata

TITLE: Latin OCR and Rescribe

DESCRIPTION: Tools for converting scanned Latin texts from images to Unicode text

NAME: Antonia Karaisl; Nicholas White

PUBLISHER: Rescribe

PLACE: [none given]

DATE CREATED: 2016-2020

DATE ACCESSED: April 5, 2021

AVAILABILITY: Free

RIGHTS: Open source under Apache License 2.0

CLASSIFICATION: digitization, Greek, language processing, Latin

Header image: A page from Martin Kraus’ Aethiopica Epitome processed using LatinOCR within VietOCR. It handles the opening chapter summary well but is only 88% accurate with the italicized body text.

Authors