Patrick Hogan

September 18, 2017

Intermediate Latin students typically encounter Latin poetry for the first time with Vergil’s Aeneid. After a brief tutorial on the rules and patterns of dactylic hexameter, they plunge in with arma virumque cano. They learn scansion not only for the sake of tradition and proper understanding of the poem, but also so that they can appreciate its rhythms and artistry—the same reasons English teachers have for teaching their students iambic pentameter for Shakespeare. The symphony of “longs and shorts” can seem forbidding to students at first, and the remedy for this is most often simply practice. Today, given the convenience of phone and tablet apps, and their potential to transform idle moments of otium into more productive ones, the Pericles Group, LLC has created the Latin Scansion App to help Latin AP students practice scanning Vergil. Aulus Gellius, who scraped together his Attic Nights from omnia subsiciva et subsecundaria tempora (“all my spare and third rate time” praef. 23), would no doubt approve.

The title screen has three main buttons: Marathon, Timed, and Achievements. “Marathon” allows the user to select a range of lines from the AP syllabus and to scan them in an untimed session.

Once the session begins, the app presents one verse at a time and the user taps either a long or a short to mark the length of each syllable. If the choice is correct, the long or short mark appears in green above the syllable, and the user earns 6 points; if incorrect, the correct mark appears in red and no penalty is assessed. The feedback is immediate, but the app does not give any hint to the user why a choice is incorrect. There is also no way for the user to fix a mistake; the app just moves to the next syllable.

The app keeps track of the user’s score and any streak of correct answers at the bottom left side of the screen. Streaks allow the user to gain multipliers (up to 4x) after at least 10 correct answers, but a single incorrect answer will break one’s streak. Because the last syllable in any line of dactylic hexameter is anceps, the app does not require the user to mark that syllable, but just presents a button to move onto the next verse.

The app’s presentation is very simple and focused: the user goes through Vergil one verse at a time, syllable by syllable. However, the app does not use scansion marks like those for the diaeresis or the main caesura; a student would find it helpful if the app automatically imposed them with each foot. The app also glosses over the irregularities that tend to occur in any long passage of Vergilian verse. For instance, at Aeneid 1.3 multum ille et terris iactatus et alto, once the user marks the first syllable of multum long, the app does not indicate that the next syllable involves an elision; when one presses the long button again, the familiar green mark appears over the –um, the elided syllable, and not the ill-. Similarly, at line 1.11 posthabita coluisse Samo hic illius arma, once one marks the –o of Samo long, the app skips ahead to hic without acknowledging the hiatus between the two words. Instances of synizesis also go unnoted: e.g., in the final syllables of Oilei (1.41) and Ilionei (1.131). Since the app covers only a selection of Vergil’s Aeneid and is aimed at students new to scanning Latin hexameters, I believe that it would be helpful for the app to give a short explanation of these not uncommon irregularities—just a sentence or two—before moving the reader along to the next verse.

The “timed” option allows the user to choose 2-, 5-, or 10-minute limits. Then the first line of the Aeneid pops up, and as in the marathon session, the app keeps track of points for correct answers and streaks until the timer reaches zero. Although the app says that the verses for timed sessions can be randomized, I was unable to discover how to do this and was forced to begin with the first line of Aeneid each time.

If the user chooses the “achievement” option, the app presents the highest streaks achieved and high score earned. There does not, however, seem to be a way for multiple people to use the app and keep their achievements separate, for there is no way to log in to the app as a particular player.

The app is inexpensive ($1.99), easy to use, and fun to play with. Students will enjoy the convenience of the app, and practicing with it will no doubt improve their speed and accuracy in scanning Vergil. [pullquote]Next time I teach Vergil, I would certainly demonstrate the app in class and recommend that my students buy it, but I would caution them to note any lines whose scansion they do not understand; the only recourse then is to a Latin instructor like myself or to a commentary.[/pullquote] More established students will be struck by its novelty and may wish to buy it to add to the games on their iPad: I have always thought that scanning Latin verse is the Liberal Arts equivalent of Sudoku.

I would, however, also show my students the comparable, yet free, Latin scansion website hexameter.co. That website has much more material than this app: there one can scan the hexameter verses of Horace, Ovid, Vergil, Lucretius, and Statius, and there is an option to scan specifically the Vergilian verses covered by the AP exam. It also gives video tutorials on scansion, which are lacking for the app, which assumes that the student has already learned the fundamentals of Latin scansion and is ready to scan straightaway. It also keeps much more extensive stats for users and even allows them to compare their achievements with those of other users. But this website too has limitations: as the name makes clear, it only deals with dactylic hexameter verse, and although especially tricky lines prompt some feedback after an incorrect answer is made—which is certainly welcome with lines of Lucretius where archaic spellings unfamiliar to novice Latin students sometimes appear—the feedback is brief and infrequent. The website also does not bother the user with scanning the last two feet of any line, despite the fact that spondaic lines are not that rare even in Vergil.

These two digital applications represent interesting and possibly useful attempts to create an online tool for practicing scansion, but I do look forward to the time when such apps can teach the finer points, give better feedback, and perhaps someday even handle iambic trimeter and Asclepiadeans.

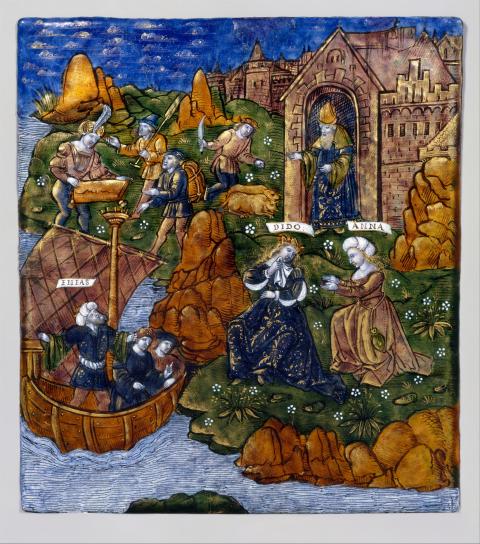

(Header Image: "Aeneas Departs from Carthage (Aeneid, Book IV)," ca. 1530–35 by Master of the Aeneid (active ca. 1530–40). Painted enamel on copper, partly gilt. Metropolitan Museum of Art 25.39.4. Licensed under CC0 1.0. Public Domain.)

Metadata

Title: Latin Scansion App

Description: App for iPad and iPhone that allows the user to practice the scansion of Latin dactylic hexameter verse through selections from Vergil’s Aeneid for the Latin AP Exam.

URL: http://practomime.com/content/scansion.php

Name: the Pericles Group, LLC; Kevin Ballestrini (direction, game design, editing); William Guida (original content); Joel Salisbury (app development); David Chanko (data development); and Stephen Slota (original artwork).

Publisher: the Apple iTunes store

Place: [none]

Collection Title: [none]

Date Created: 2014-2017

Date Accessed: July 5, 2017 (version 1.12)

Availability: $1.99 (requires iOS 6.0, compatible with iOS 9)

Rights: [none]

Classification: Latin, scansion, hexameter verse, language learning tools, games, mobile applications, pedagogy, texts.

Authors