Robert Gorman and vgorman1

February 27, 2017

How many times have you stood in a classroom, trying to figure out a way to diagram coherently a Latin or Greek sentence on the board in order to clarify a structure that is baffling your students? Why not do the same thing digitally, and even require the students to construct their own sentence trees to demonstrate their understanding of the problem? A few years ago, we learned about a program to do just that. Arethusa is a set of tools developed by the Alpheios Project, adopted by the Perseus Digital Library, and delivered by the Perseids editing platform. We began using these syntactic trees in my advanced Latin classroom and were so pleased with the results that we soon introduced them to classes at all levels, from the second week of Latin 1 to the research capstone for majors.

In elementary classrooms we set Arethusa to require students to supply all morphological and syntactic information. The labels for grammatical categories can be adjusted according to the chosen textbook or the needs of the students. If this year’s textbook says “ablative of means” while last year’s had “instrumental ablative,” it is no matter, since Arethusa makes the alteration easy. At the intermediate level, treebanks can supplement (or even supplant) the student commentary. The instructor can provide students with analyses of tricky sentences with some or all of the morphology identified and syntax annotated. For example, a fully labeled sentence from Horace’s Ars Poetica would look like this:

All grammatical relationships are identified in the terms the students are used to seeing. Students translate and are asked to explain the syntax indicated. Why, for example, is iungere a Complement Clause rather than an Indirect Statement? What are the relevant criteria? As the semester progresses one can gradually provide less and expect more, until the students are producing full-fledged dependency trees of their own. Such assignments provide much information about how students are doing, but of course it is difficult to grade them without nodding off and making mistakes. Mirabile dictu, the Arethusa system does this work automatically, checking student efforts against the instructor's own version and displaying the results in detailed reports.

The use of such treebanking has increased the detail and exactitude we can expect in student work. Many of the best students love the approach and often ask if they can continue to treebank after the semester is over.

For the instructor, grasping the essentials of treebanking is not difficult. Reading the guidelines and mastering the logistics of Arethusa takes about a half hour. The construction of dependency trees themselves is about 95% straightforward, just as grammar is about 95% unambiguous. However, that remaining 5% is as complex as linguistics itself. We have all puzzled over obscure constructions for hours and days (otherwise we wouldn’t be classicists). But more importantly, the effort involved in resolving ambiguous cases has led us to frame questions about grammar and linguistics that were more sophisticated than before.

Treebanking likewise had a significant impact on our scholarly work. In our book about the idea of the corrupting influence of luxury as characterized in Greek historiographical traditions, we had developed a method to evaluate the authenticity and reliability of out of context quotations, historiographic fragments where no original context by a given author was preserved. We used a philological microanalysis comparing diction within a fragment to that of the transmitting author (usually Athenaeus), in a series of miniature authorship attribution studies. In the midst of our new interest in treebanking, we realized that we could approach old research problems in new ways. Our central research question now is, “Can we determine authorship (or accuracy in text reuse) based entirely on syntax and not vocabulary?” This leads to a series of traditional philological questions that are now able to be addressed in new ways using treebanking: What are the syntactic tendencies of individual authors compared to the norm? What constructions does each one favor and avoid? Can we determine the degree and manner of imitation of classical authors by the writers of the Second Sophistic movement? What are the structural influences of Latin grammar on later Greek writing (frequency of verbal adjectives, asyndeton, etc.)? Can we determine if works generally thought to be wrongly attributed to an author are indeed spurious?

[pullquote]We now have an open access database of some 300,000 words of treebanked Greek prose that we added to the 360,000 words of verse already available in the Ancient Greek Dependency Treebank (AGDT), under the auspices of the Perseus Digital Library.[/pullquote] It turns out that syntax alone is an excellent tool to discriminate among authors. Our method has proven surprisingly accurate even for text segments smaller than 50 words. These results encourage us to believe that quantifiable syntactic data will, before too long, become an integral part of the evaluation of fragments and other related questions.

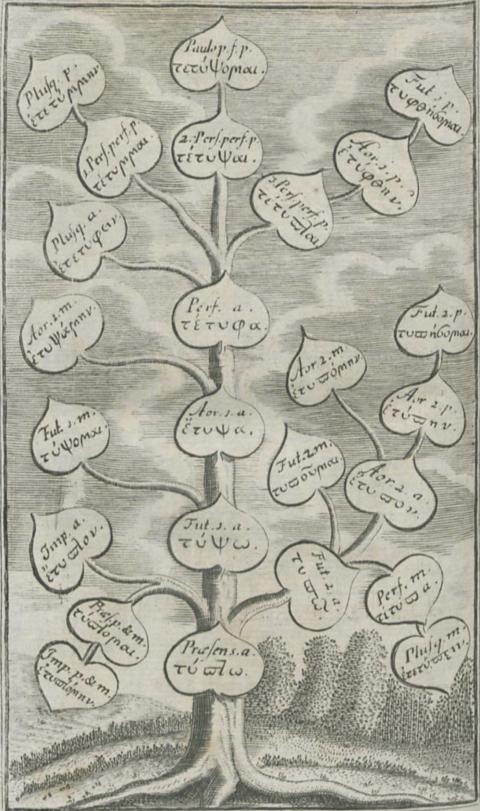

(Header Image: Frontispiece from Erleichterte Griechische Grammatica by Joachim Lange, Johann Heinrich Schulze, and Christian Gottlob Liebe (Halle: Waisenhaus, 1740). Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg Library. Public Domain {{PD-1996}}.)

Authors