Richard Armstrong and Elizabeth Vandiver

February 15, 2023

Richard H. Armstrong and Elizabeth Vandiver are longtime members of the APA/SCS, and they are among those scholars who have long fostered an interest in bringing more focus on translation to the annual meetings. In this post, they look back on the history of translation panels and how they have changed over the years.

Richard Armstrong: You know, Elizabeth, as we listened to the amazing papers in the panel Translation and the Visual at the most recent SCS meeting in New Orleans, I was reflecting on how far we’ve come on the topic of translation from the days of the old APA. I remember the first panel on the topic I ever attended, your Choosing a Translation: What is at Stake? (1996), which left me feeling how weird it was that translation wasn’t a more prominent topic at the APA meetings. After all, philologists are all about detailed linguistic study and historical/social context. Your panel had a nice mixture of translators (Sarah Ruden and Peter Meineck) and translation scholars (David Wray and Steven J. Willett), and your respondent, Peter Green, had been a translator most of his life — in fact, he’s now just translated Homer in his nineties! And yet, at that 1996 panel, Green surprised us by basically saying translation theory was bunk and the papers seemed beside the point, as if translation is something self-evident and uncomplicated. My shock at that led me to ask you if we couldn’t do more on the topic, do you recall?

Elizabeth Vandiver: I do indeed recall. I don’t think Peter Green was saying that translation was “uncomplicated,” exactly, but he certainly did not have much time for any of the points the papers raised.

When I decided to organize that panel, I’d been teaching for about seven years. My first jobs were contingent positions, and almost all my courses were large classical culture classes taught entirely in translation. I remember being very struck by two things: first, that my students in those classes would know the ancient authors only through the translations that I assigned them; and second, that while the “Homer” one meets in (say) Fitzgerald’s Odyssey is very different from the Homer one meets in Lattimore’s, none of my professors in grad school and none of my colleagues ever talked about that, or about how to pick a translation for classroom use, or about what aspects of each translation might be most important for specific kinds of classes. Hence the subtitle of my panel: What Is at Stake?

At that point, I was almost entirely ignorant of translation theory; I was interested mainly in the pedagogical issues of how to decide which Homer, which Virgil, which Catullus, which Sappho my students would encounter. I was both energized and frightened by your suggestion that we should try to “do more on the topic.”

RA: My own point of view was more typical of someone coming from the comparativist perspective. I was raised in both Romance and Classical Philology, so my orientation was very reception-oriented from the start. Someone who looks at classical authors as I do, from the standpoint of the Middle Ages and Renaissance, cannot unthink translation from the “Classical Tradition.” In fact, such engagements have been crucial to the formation of modern languages. But to be honest, my own irritation was then — and remains — the relative lack of integration of translation studies with reception studies. So I am as eager as ever to keep stirring this pot.

We were fortunate in those days that the old APA had a “3-year colloquium” option, where interested parties could create organizer-refereed panels on a sustained topic over three years. We went that route with a pretty simplistic division into poetic genres: epic (1998), lyric (1999), then drama (2001). Using genre as an organizing principle seems rather unsophisticated to me now, but it reflected the basic way we think of ancient poetry, and it kind of worked — don’t you agree?

EV: I thought it worked very well, in fact. We attracted very different audiences in each year, which kept the sessions interesting and lively and avoided the possible perception that we were just doing the same thing over and over. I no longer have copies of our old CFPs, but from the start, we were open to papers on translation into any language, and that meant that, over the years, we had papers on translation into early modern Spanish, French and Italian; modern and Byzantine Greek; Dutch and Flemish; Bulgarian; and even Arabic, which also helped avoid any perception of dullness and, I think, was very useful for shaking up some of our unconscious Anglophone biases.

RA: And that diversity came without any special pleading. People found our CFP and submitted work in progress. Folks can see some of that in the special issue of Classical and Modern Literature we co-edited, “Remusings: Essays on the Translation of Classical Poetry” (27.1, 2007). Now, however, we can see there was still a lack of truly global diversity in our approach — nothing into East Asian or South Asian languages, nothing at all about translation into African languages, or the vibrant world of translation in Latin America. But we did manage to create a space for thinking about a greater variety of contexts for translation, and I think we can remain proud of that. On the other hand, don’t you think we would never have dreamed about the kinds of things people present nowadays?

EV: I certainly wouldn’t have dreamed of how the term “translation” has broadened out! For me, reading Lorna Hardwick’s Translating Words, Translating Cultures was revelatory, and began pointing me towards thinking of translation as, indeed, a form of reception. I agree with you that we can remain proud of our role in bringing translation into the realm of subjects that the SCS and our profession consider worth discussing, and I am very encouraged that the SCS now has a Committee on Translations of Classical Authors. That Committee sponsors annual panels, generally alternating between scholarly panels and workshops (the CFP for next year’s is out).

We were able to renew our colloquium for an additional three years, which we focused on prose, again divided by genre (Prose Fiction; Rhetoric and Historiography; Philosophy). Did you think the genre division worked as well for prose as for poetry?

RA: In terms of organizing panels and channeling interests, I would say it worked pretty well, but the striking thing that emerged from it was that prose just doesn’t excite the same level of critical or theoretical interest as poetry. With poetry, one can think of the text on the visceral, rhythmic level, as well as in terms of meaning, narrative, or other features. But prose is…prosaic as a topic. We all know it is not true that prose has no poetics, no style — how could you have a classical education and think that! But, for whatever reason, translation into prose seems to set off fewer alarms. On the other hand, I felt our final panel on the translation of philosophy was especially exciting, and it again left me with the feeling that we had only scratched the surface.

I think the new approaches to translation we are seeing at SCS arise more organically from the very different perspectives and urgencies felt by our profession. Popular culture and the media of film, the graphic novel, newer forms of performance and visual art…these not only change how one thinks of translation by stepping away from the language A → language B model; they also provide new contexts where issues of race, gender, class, and power enter into the discussion. It seems to me that these new discussions truly are useful to current SCS members. I was especially impressed by the warm reception of Julia Perroni’s paper, “Helen in Trans-lation: Putting a Trans Helen on Stage,” because her project is both creative (based on her own work) and reflective of the totally new ways gender and identity are conceived these days.

EV: I’m still rather traditionalist at heart, and I still think there’s a useful distinction between translation and adaptation; but I agree that issues which are urgent for our profession overall are also opening up new perspectives on translation. This can be true even in a discussion of translation that still adopts the language A → language B model. Last year, I gave a paper for the Herodotus Helpline that focused on how to deal with issues of race, ethnicity, and gender in translating Herodotus — e.g., how to translate barbaroi? Recognizing such questions as crucial to translation (as Emily Wilson’s Odyssey and Stephanie McCarter’s Metamorphoses both do) is a real change from past practice.

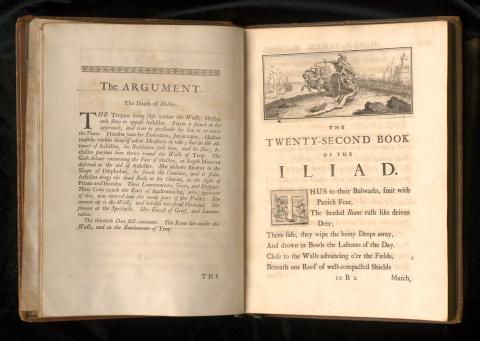

RA: I still adhere to the notion that “translation” is a cluster concept or a spectrum of practices. It makes sense that philologists are keen on text-to-text framings, since they are easier for purposes of comparison. But I think a lot of new work challenges us to get past our logocentric assumptions. I found it very helpful to think about Alexander Pope’s original subscriber editions of Homer as a “total work of art,” in line with current work on the materiality of translation and book history that makes the topic fun for even the most traditional scholar. But don’t you feel another byproduct of the discussion of translation is to open our field’s traditional strengths in ways that connect to other disciplines?

EV: Yes, certainly. Perhaps paradoxically, because increasingly fewer historians of, say, the Renaissance or the Reformation or the Spanish colonial presence in the Americas are able to read Latin fluently, colleagues from those fields will more and more have to rely on classicists for translations of primary texts from those eras. Revisiting my 1996 question, “What is at stake?,” classicists will need to think not just about choosing translations for our survey courses, but also about crafting translations that will become primary source texts for other disciplines. All the more reason, then, for us to continually examine our own expectations and assumptions about translation. In that regard, I found the recent SCS workshop Making Space for Translation particularly engaging and encouraging.

One area that I think will need more careful attention is the pedagogy of translation. Current members of the Committee on Translations of Classical Authors are interested in highlighting pedagogy in some future SCS panels. Workshops or panels might discuss translation pedagogy from several angles, including issues involved in:

- teaching with and through translation

- offering graduate and undergraduate translation workshops

- classes dedicated to translation (theory, history, practice)

As ever more students, historians, theatre practitioners, artists, novelists, poets, and others access Classics only through translation, rich discussion of and engagement with the theory and the practice of translation should receive much more attention in our field than has been the case so far. Almost three decades after you and I organized our colloquia, translation studies are moving (slowly!) closer to the front and center of our profession’s attention. I’m hopeful that this trend will continue.

RA: Me too! And the veering of the SCS from an exclusively Anglophone worldview is underway thanks to the new Hesperides group that focuses on Hispanophone and Lusophone reception. Their panel for 2024 is also on translations. See you next year!

Header image: Original subscription edition of Alexander Pope’s Iliad. Courtesy of Special Collections, M. D. Anderson Library, University of Houston.

Authors